1880

1881

1882

1883

1884

1885

1886

1887

1888

1889

BOAT RACE 1880 - 1889

Oxford University v Cambridge University

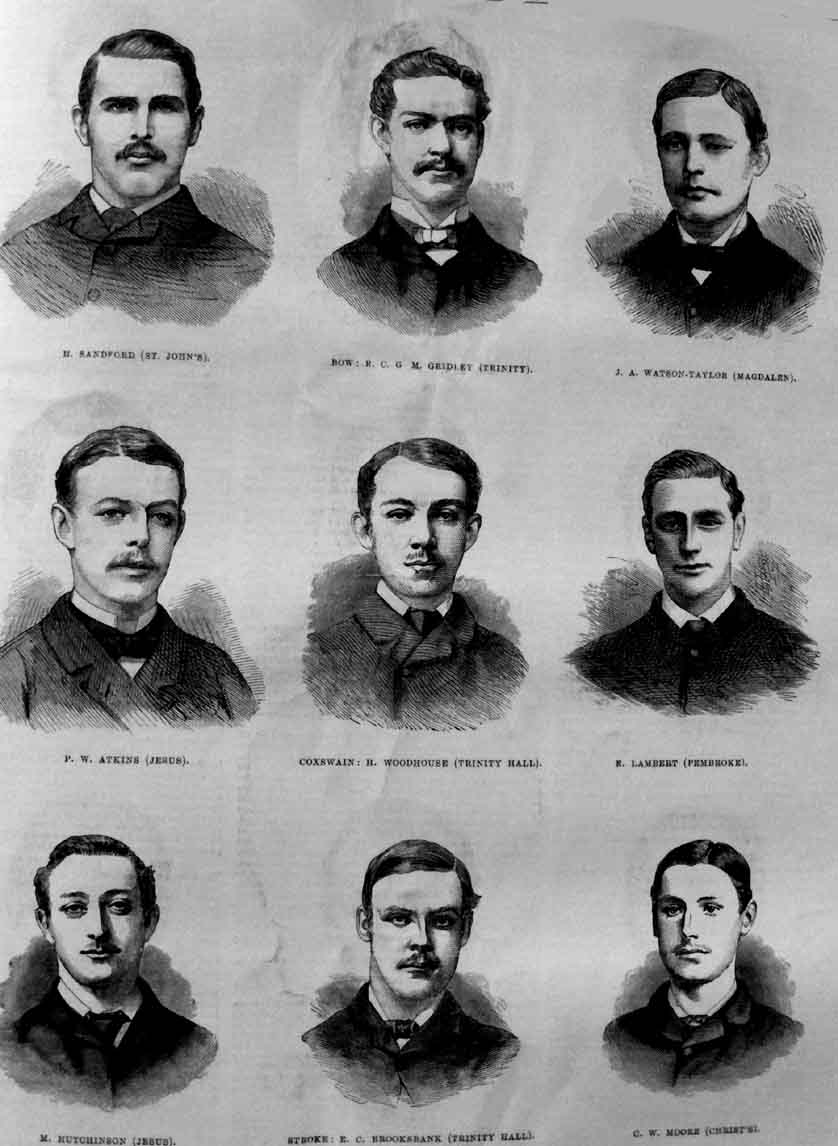

Map

Map taken from George Drinkwater's "The Boat Race"

37: 1880, Monday, 22nd March

In 1880 OXFORD WON by 3¾ lengths. Time 21 minutes and 23 seconds. Oxford 19, Cambridge 17

Oxford had problems in training whilst Cambridge initially looked good.

The race was to have been on Saturday March 20th but the fog was too thick, so it was postponed

until Monday, 22nd March.

There was a poor tide and a strong east wind. Oxford won the toss and chose Middlesex.

Cambridge started well and led, but Oxford at a lower rating gradually caught them.

At Chiswick Reach, Oxford raised their rating and moved past Cambridge to

win by 3¾ lengths.

Bow 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stroke Cox |

OXFORD 1880 R H Poole, 10. 6 D E Brown, 12. 6 F M Harbreaves, 12. 2 H B Southwell, 13. 0 R S Kindersley, 12. 8 G D Rowe, 12. 3 J H T Wharton, 11.10 L R West, 11. 1 C W Hunt, 7. 5 |

Bow 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stroke Cox |

CAMBRIDGE 1880 E H Prest, 10.12 H Sandford, 11. 5½ W Barton, 11. 3½ W M Warlow, 12. 0 C N L Armitage, 12. 2½ R D Davis, 12. 8½ R D Prior, 11.13 W W Baillie, 11. 2½ B S Clarke, 7. 0 |

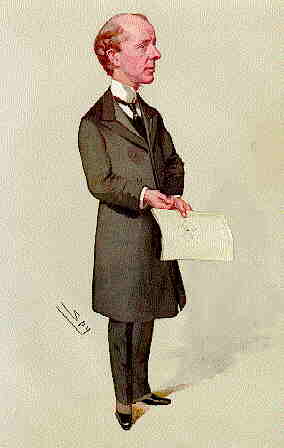

Oxford President and 6, George Duncan Rowe

and later a Henley Regatta Steward

The Boat Race according to Charles Dickens Junior. He suggests holding it elsewhere! -

A quiet, friendly sort of gathering ...

Not many years ago the annual eight-oared race between the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge

was an event which concerned only the crews, their friends, the members of the Universities,

and that small portion of the general public which took pleasure in river sports.

It was a quiet, friendly sort of gathering enough in those days.

The comparatively few people who watched the practice of the crews all seemed to know each other.

It was a wonderful week for parsons.

Past University oarsmen, their jerseys exchanged for the decorous high waistcoat, the white choker

taking the place of the rowing-man's muffler, were to be met all over Putney,

and about Searle's yard and the London Boat-house.

The towing-path was a sort of Rialto or High Change, on which old friends who had rowed in the same

boat years ago, and had since gone down into the struggle and fight of the world by many different

paths, met and renewed their youth as they talked over old times, and criticised their successors.

There were but few rowing-clubs then; the river had not become the fashion; the professional touts

and tipsters had not fastened on the boat-race; the graphic reporter as yet was not.

There was betting, of course - wherever Englishmen are, there is betting of some sort -

but it was of a modest kind, and was unaccompanied by publicity.

The whole thing. had the ring of true sport about it.

It seemed indeed to be the only event that kept alive that idea of sport for its own sake

which was fast fading out, if it was not already extinct, in most other contests.

Of course it was all too good to last...

The popularising process which has gone on with everything else was not likely to spare the boat-race.

First of all aquatics generally grew more in favour, and so a larger public was attracted to

take an interest in the battle of the blues. Then the newspapers took the subject up, and the

graphic reporter worked his will with the race and its surroundings, and the extraordinary

multiplication of sporting newspapers and sporting articles in papers of all sorts,

let loose any number of touts on to the towing-path.

Finally the ominous announcement of "Boat-race, 5 to 4 on Oxford (taken in hundreds)", and the like,

began to appear in the price current of Tattersall's; and the whole character of the race was changed.

What the blue fever is now, and has been for some years, every Londoner knows well.

Perhaps it is because the boat-race is the first of the spring events -

as it were, the first swallow which indicates at least the possibility of a summer -

perhaps it is because of the very natural readiness that exists among the masses to take advantage

of any excuse for a holiday; perhaps it is because of the sheep-like tendency of the British

public of all classes to follow a leader of any kind anywhere, that the complaint assumes so epidemic

a form with every recurring spring. It is certain, at all events, that for some time before the race

there is taken in it - or affected to be taken, - which does just as well - an interest

which has about it even something ludicrous.

Every scrap of gossip about the men and their boats, their trials and their coaches,

is greedily devoured. Year by year, to gratify the public taste in that direction, has the language

of the industrious gentlemen who describe the practice become more and more candid, not to say personal.

The faults and peculiarities of individual members of the crews are criticised in some quarters

in terms which might be considered rude if applied to a favourite for the Derby,

who presumably does not read the sporting papers, and which, when used in speaking of gentlemen

who may perhaps have feelings to be hurt, seems to the unprejudiced mind even offensive.

The gushing reporter not only attends the race itself, but disports himself on the towing-path

after his peculiar and diverting fashion on practice days, and daily develops the strangest

conglomeration of views on matters aquatic in the greatest possible number of words.

All sorts of dodges, borrowed from some of the shabbiest tricks of the "horse watcher's" trade,

are adopted by touts, amateur and professional, to get at the time of the crews between certain

points, or over the whole course. The race is betted upon as regularly as the Derby, as publicly,

and as generally.

Cabmen, butcher boys, and, omnibus drivers sport the colours of the Universities in all directions:

the dark blue of Oxford and the light blue of Cambridge fill all the hosiers' shops,

and are flaunted in all sorts of indescribable company.

Every publican who has a flag-staff hoists a flag to mark his preference and to show which way

his crown or so has gone - unless, as is sometimes the case, he be a dispassionate person with

no pecuniary interest involved, in which case he impartially displays the banners of both crews.

Everybody talks about the race, and it generally happens that the more ignorant of the matter

is the company the more heated is the discussion, and the more confident and dogmatic the opinions

expressed.

That thousands and thousands of people go down to the river on the important day who do not know

one end of a boat from the other, who have no prospect of seeing anything at all, and no particular

care whether they do see anything or not, is not surprising.

That other thousands go, knowing perfectly well that all they are likely to see is a mere glimpse

of the two crews as they dash by, perhaps separated by some boats' lengths after the real

struggle is all over, is equally natural.

Thousands and thousands of people go to the Derby on exactly the same principles.

That 'Arry has claimed the boat-race for his own is only to say that he is there as he is everywhere,

and that circumstance is not perhaps to be laid to the charge of the boat race.

But the fact is, and becomes more and more plain every year,

that the boat-race is becoming vulgarised - not in the sense that it is patronised

and in favour with what are called "common people," but in the sense that it has got to be

the centre of most undesirable surroundings - and that its removal from metropolitan waters

would not be lamented by real friends of the Universities, or lovers of genuine sport.

It is not so bad as the Eton and Harrow cricket-match, which has been utterly vulgarised by "society,"

genuine and sham, and for which there is no kind of excuse or reason.

So race somewhere else ...

Then University crews cannot meet each other on their own waters, as cricketers can play upon

each other's grounds. They must have a neutral course to row upon

It is probable, before very long, that it will occur to the authorities that there are

other suitable pieces of water in England besides the Putney course,

and that there is no reason whatever why, if the annual vexata quaestio of the rowing superiority

of the rival Universities is all that is to be taken into account,

the race should not be rowed elsewhere.

The managers of the race or their friends have shown signs of some confusion of mind on this head

on more than one occasion. Protests have gone forth that it is a private match with which the

public have nothing to do. The crowding of spectators to see the practice - and as many people go

nowadays to Putney on a Saturday afternoon if there be a good tide, as used to go to the race itself

twenty years ago - has been complained of.

The general exhibition of interest has been deprecated. It has been intimated that all this

newspaper publicity is distasteful and undesirable. In some strange way the boat devoted to the

service of the general body of the press on the day of the race is always either so slow a tub

as to be of little use, or else meets with some mysterious accident which deprives its occupants

of any but a very distant view of the proceedings, while their more fortunate brethren,

who happen to have been educated at Oxford or Cambridge, are careering gaily after the racing

boats on board one of the University steamers. The independent sporting papers say that accurate

information has become more and more difficult to get, and newspaper reports -

except in special quarters - are, following out the private-match theory, discouraged as much as

possible. But it is all to no purpose. The boat-race can never shake off its surroundings so long

as it continues to be rowed at Putney. Change of air will, in all probability, shortly be found

necessary to restore it to a healthy condition - a condition in which it certainly is not now.

As matters stand at present ...

As matters stand at present the race is rowed annually, about the Saturday before Passion Week, between Putney and Mortlake, usually with the flood-tide, although occasionally the reverse course has been taken. The crews are generally at Putney for a fortnight or more for practice, a very much longer period of training on the tidal water being considered necessary now than was the case in the earlier years of the match. Four steamers only accompany the race: one for the umpire, one for either University, and one for the press; and although this arrangement is decidedly an advantage from the point of view of the public safety, the spectators about Hammersmith and Barnes lose a singular sight. The charge through the bridges of the twenty steamers or so which used to be chartered to accompany the race was something to see; but although it was magnificent it was not safe, and it was fortunate that the Conservancy regulations stopped it before some terrible accident occurred. That nothing very serious ever happened in that fleet of overcrowded swaying, bumping, jostling boats was an annual cause for wonder; and it became sometimes, when one was on board one of the fleet as it approached Hammersmith, matter for rather serious consideration to speculate at what particular moment the mass of spectators on the suspension-bridge would break it down and plunge with the ruins into the river. Fortunately the bridge stood long enough for the official mind to be exercised on the subject before anything happened, and it is now wisely closed during and for some time before the race. The best points of view are at Chiswick, on Barnes Terrace, or, best of all, perhaps, on Barnes Railway-Bridge, tickets for which are to be had at Waterloo Station. Otherwise, railway travelling between London and Mortlake cannot be recommended on boat-race days - for ladies at all events.

The Universities rowed their first match over a course of two miles and a quarter at Henley, and have met 35 times over the London course, as will be seen by the subjoined table, with the result that each University has won 17 races, while the race of 1877 was given by the judge as a dead heat. It is significant of the kind of influences that now prevail that this decision was productive of much discontent, and that the judge, who had officiated for a long period, was in the following year superseded. Of course all sorts of improvements have been made in the boats in which the competitors row, the introduction of outriggers in 1846 and the adoption of sliding-seats in 1873 being the most radical alterations ; but it is noticeable that from some cause or another the sliding-seats, which the modern rowing-man looks upon as an absolute necessity, do not seem to have increased the pace of the boats - if the time test goes for anything, that is to say. This is the more remarkable, as rowing men appear to be agreed that a crew rowing in fixed seats would have no chance against opponents of exactly equal merit on slides. It may be that the times taken before the days of chronographs were not exactly trustworthy. However it may be explained, the fact remains.

Cyclic success ...

It will be seen that success has often favoured one or other of the Universities for a series of years, only to go over to the other side for another series. The most important consecutive score is that of Oxford, from 1861 to 1869. This is what may be called the Morrison era, as the brothers Morrison were either in the boat or coaching during the whole, or the greater part, of that period, and finer crews than some of those which comprised such men as Darbishire, Willan, Tinné, the Morrisons, Hoare, Yarborough, Woodgate - to mention only a few names - have never been sent to Putney. Then Cambridge, who had persevered with the utmost pluck through most disheartening difficulties and defeat, learnt the proper lesson from Morrison, and the light blue once more came to the front under the auspices of Goldie. After this admirable stroke and sound judge, who did wonders for Cambridge rowing, came Rhodes, and plenty of good men have since been found to do battle at Putney for the honour of Cambridge.

Charles Dickens (Jr.), Dickens's Dictionary of the Thames, 1881

FIFTHIETH ANNIVERSARY BANQUET

1881: On the night before the race the Jubilee Anniversary dinner was held -

ON THE BANQUET HELD

IN COMMEMORATION OF THE FIFTHIETH ANNIVERSARY

OF THE UNIVERSITY BOAT RACE, APRIL 7, 1881

Sing we now the glorious dinner

Served in grand Freemasons' Hall;

Welcome loser, welcome winner,

Welcome all who've rowed at all:

Oarsmen, steersmen, saint or sinner,

Whet your jaws, and to it fall.

Fifty years and more have rolled off

Since the race of 'Twenty-nine':

Therefore all, by death not bowled off,

As of yore, your strength combine,

And in gangs of nine be told off -

Not to paddle, but to dine.

Oh! what hands by hyands are shaken!

Bishop, Dean, Judge, Lawyer, Priest,

Bearded soldier, beardless deacon,

Men still scribbling, men who've ceased;

Court, church, camp, quill, care forsaken,

Muster strong and join the feast.

Staniforth, with air defiant,

Captain of the earliest Eight;

Toogood, amiable giant,

Unsurpassed in size and weight;

Merivale, one too reliant,

But for years resigned to fate; -

[ Staniforth: 1829 Oxford Stroke - later Rector of Bolton-by-Bolland ]

[ Toogood: 1829 Oxford 5 - later Prebendary of York ]

[ Merivale: 1829 Cambridge 4 - later Dean of Ely ]

Scores on scores, from these descended

In aquatic lineage, came;

Cantabs with Oxonians blended,

Ancients some - some new to fame:

But my song would ne'er be ended

Were I every one to name.

Happy was the thought that seated

Mate by mate, crew facing crew;

Well ye know who have competed

In what'er 'tis well to do,

How that man is ever greeted

(Friend or foe) who rowed with you.

Fitly o'er the feast presiding,

All-accomplished Chitty sits,

Through the toasts how neatly gliding,

Winning cheers, redoubling hits -

Not of bat with ball colliding -

Merely sympathy of wits.

[ Chitty: 1849(twice!), 1852 Oxford two, four then stroke and president ]

Yet another, more sonorous,

Rules our Chief, and checks our Chair,

Stills the hum, and quells the chorus,

Moderates the loud 'Hear! Hear!'

Coolly acts the despot o'er us,

As o'er Sheriff or Lord mayor.

Now the turtle disappeareth,

Now the turbot is dispatched;

Sparkling wine our spirit cheereth;

Well are Cam and Isis matched,

While each man his platter cleareth

Of the fishlets barely hatched.

Then comes talk of winning, losing,

Fouling, 'crabs' untimely caught,

Sinking, catching the beginning,

And of all Tom Egan taught,

Morrison or Shadwell, spinning,

Yarns of deep aquatic thought.

[ Tom Egan: 1836, 1839, 1840, Cambridge Cox and influential coach ]

Such the converse - not unbroken -

Some of training would discourse,

But that band (of 'vis' the token),

While each course succeeds to course,

(Ophicleide, als! bespoken),

Silences each tongue by force.

Now our hunger hath been sated,

Now with ice our lips been cooled,

And the Chairman well hath stated

How this realm is nobly ruled,

And our Queen and all related

Do their duty wisely schooled;

Great the toasts, and great the cheering;

Thrice times three and thrice again,

Every man his voice uprearing

To the band's assenting strain,

Loyal strain of men God-fearing

In this Isle that rules the main,

Now 'The Chair', succinctly noting

How whate'er is good or great

Follows from successful boating

In the Church, the law, the State,

Instances of each kind quoting

Some more early, some more late.

Turns triumphant to the guernsey,

By a reverend Prelate sent;

Reads, 'that though to come he burns, he

Must not come or he'd repent,

For that, whereso'er he turns, he

Duties finds because 'tis Lent.'

[ Charles Wordsworth: 1829 Oxford 4. Later Bishop of St Andrews 1853 - 1892 ]

Rogers next (how grand of feature,

Broad of shoulder, deep of chest!),

Brimming over with good-nature,

Tells the tale which wrings our breast,

How that horse (poor blundering creature!)

Well-nigh sent him to his rest.

[ Rogers: 1840 Oxford 4 ]

Toogood (once too good for Granta)

Brings his guernsey on his back,

Then like some gigntic planter,

Gives his chest a hearty smack,

And with reverential banter

Deigns a modest joke to crack.

Merivale, historian famous,

Proves that Cambridge would have won

Had not fate resolved to tame us,

Had not sons of Isis done

Better e'en that sons of Camus

In that Boat Race number one.

Up rose Brett, once seven to Stanley,

Every inch the Judge - the man:

Upright, downright, comely, manly

(Beat him Oxford if you can!),

All that's brave and gentlemanly,

Since to row he first began.

[ Brett: 1839 Cambridge 7 ]

[ Stanley: 1839 Cambridge stroke ]

Turn your eyes to that third table,

Where - still sound in wind and limb -

Stands that Smith who, quite unable

(More shame for him) then to swim,

Sank - yet lives! Oh, fate too stable!

Loftier end's in store for him.

[ A.L.Smith 1857, 1858, 1859(Sank) Cambridge 4, 2, 3. Later Judge of the High Court. ]

Next 'the Navy and the Army',

And his well-loved 'Volunteer',

Chitty toasts; and with a charm he

Has alone, provokes a cheer,

While, with true Etonian calm, he

Three Etonians bids appear.

Reggie Buller, brave Crimean;

Hornby, brother of the bold

Sailor mediterranean;

Warre, whose sway is uncontrolled,

Naval, martial, Herculean,

Scorning heat, defying cold.

[ R J Buller: 1852 Oxford 4 ]

[ Hornby: 1849 (December) Oxford bow ]

[ Warre: 1857, 1858 Oxford 6 then 7. Later Headmaster of Eton (with 'sway uncontrolled'!) ]

Men like these still make it truthful

To repeat the Great Duke's boast,

That these struggles of the youthful

Helped to victory that host,

Gallant, active, brave and ruthful,

Whom Old England honours most.

Once again (the chair desiring)

Denman toast these Fathers three

Who convinced a world admiring

That this eight-oared race should;

Once again (the theme inspiring)

'Nine time nine, and three times three'.

Up rose Staniforth, 'the father',

Spoke of those untimely gone

To the stream Elysian - rather

'Of the stroke they once put on ' -

Most portentous (as we gather),

Like the seats they sat upon.

'Temporis laudator acti',

So the young and thoughtless said;

I said nothing, but in fact I

Thought 'twas time to go to bed,

Yet another toast still lacked, I

Mean 'The caterers of this spread'.

These are hounoured. Then to Chitty

Warbling cheers, the best we know -

Best of chairmen, brave wise witty,

Full of goodness, full of go,

Q.C., M.P. (Oxford City)' -

Off to bed we gaily go.

Blest, thrice blest, is such revival,

Blest the man who can enjoy

Scenes like these, no mere survival,

For the man recalls the boy,

Hon'ring most his staunchest rival,

Hon'ring now without alloy.

Thus in generous emulation

Cam and Isis both are one;

Thus each passing generation

Earns the meed of duty done;

Thus the glory of our nation

Shines wherever shines the sun.

38: 1881, Friday, 8th April

In 1881 OXFORD WON by 3. Time 21 minutes and 51 seconds. Oxford 20, Cambridge 17

Illustrated London News -

The practice of both crews was carried on under great difficulties last week, owing to the fearfully rough state of the river,

and on Monday the Cambridge boat was very nearly swamped below Putney Bridge.

Each crew has had several trials with scratch eights, and, on the whole,

they can scarcely be said to have passed the ordeal favourably,

as they have not been able to get away from their opponents until superior condition told its inevitable tale.

The "light blue" is certainly the prettier crew to look at, and has done the better times over the course;

but the betting - an infallible guide in this race - points to success of Oxford.

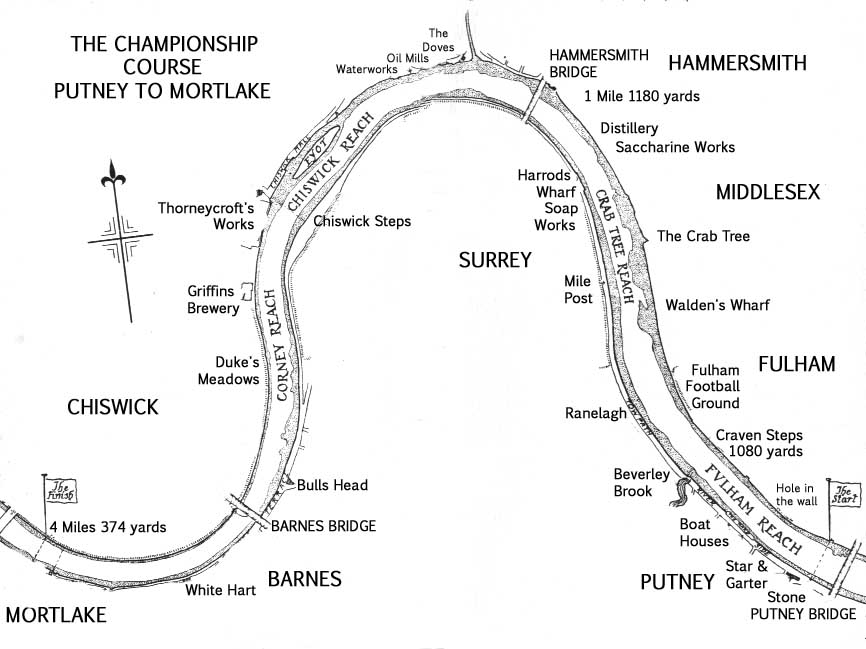

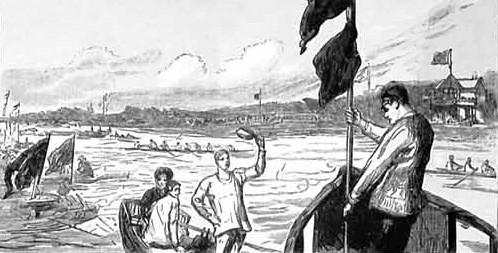

Spectators 1881, by Henry Furniss -

Spectators, 1881

Illustrated London News -

The popular mind of London yearly gets into a fit of more or less affected excitement,

upon the favourite occasion that comes off on Friday morning, as usual,

along the famous rowing-course of the Thames, from Putney to Mortlake, where Oxford and Cambridge champion eights,

the "Dark Blues" and the "Light Blues", pull against each other for the honour and glory of their respective Universities.

It is not a little remarkable that the declaration of a zealous sympathetic partisanship

for one or other of those learned and reverend academical corporations,

the two ancient English Universities, should be most frequently uttered

by the mouths of babes and sucklings, of servant-maids, of errand-boys, and the illiterate streetocracy,

who can have no possible reason for partiality to either serene abode of classic studies.

"Are you Oxford or Cambridge?" these simple folk demand of every one they meet, as if it were a contested election,

when one is supposed to be Liberal or Tory, and to know the reason why, unless one has a still better reason for not

being one or the other. It is like the fuss about "the Derby" used to be,

among people whose actual knowledge of horses was equally naught with their knowledge of boat-racing,

and whose real concern and interest therein was not less remote.

For all that, we are bound to confess that the Epsom Downs, on a fine Wednesday of early summer, with some fifty thousand

Londoners making holiday there, afford a magnificent sight;

and nearly the same is to be said of the crowded banks of our river on the Friday morning,

though to soon in the spring season to escape a perilous chilliness of the air,

when the rival "Blues" exhibit their manly prowess in a competion of aquatic swiftness.

Bow 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stroke Cox |

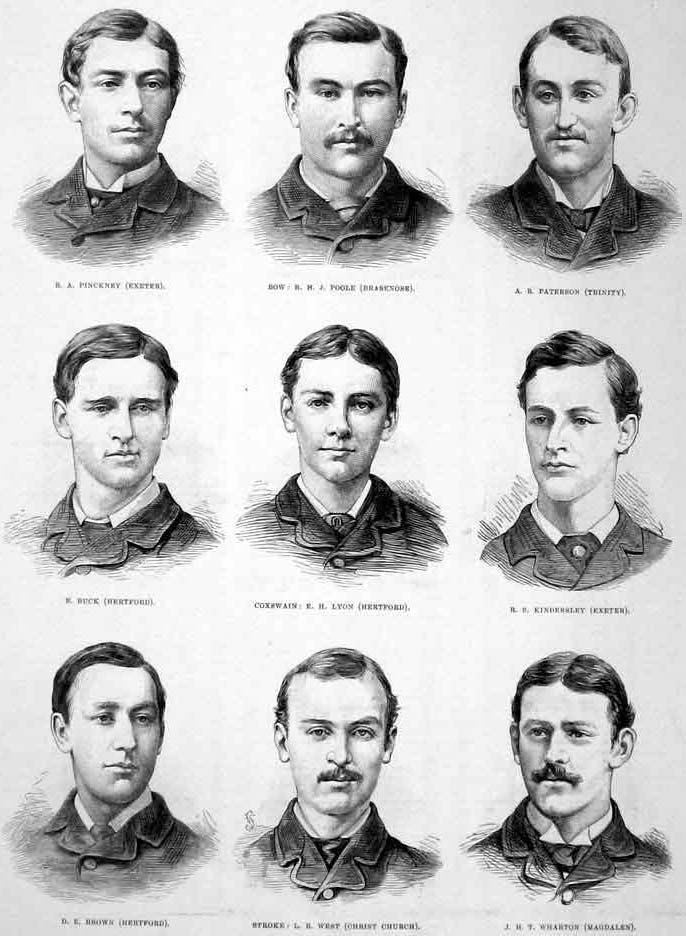

OXFORD 1881 R H J Poole, 10.11 R A Pinckney, 11. 3 A R Paterson, 12. 7 E Buck, 11.11 R S Kindersley, 13. 3 D E Brown, 12. 7 J H T Wharton, 11.10 L R West, 11. 0½ E H Lyon, 7. 0 |

Bow 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stroke Cox |

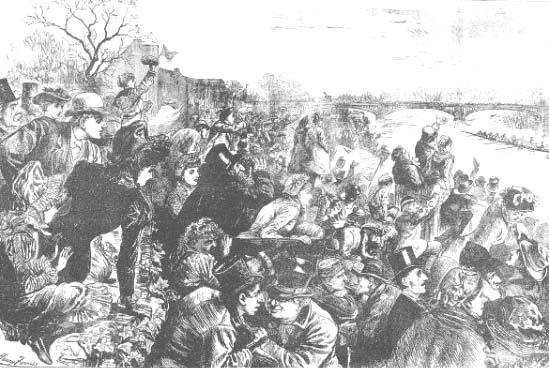

CAMBRIDGE 1881 R C M G Gridley, 10. 7 H Sandford, 10.10½ J A Watson-Taylor, 12. 3½ P W Atkin, 11.13 E Lambert, 12. 0 A M Hutchinson, 11.13 C W Moore, 11. 9 E C Brooksbank, 11. 8 H Woodhouse, 7. 2 |

|

|

39: 1882, Saturday, 1st April

In 1882 OXFORD WON by 7 lengths. Time 20 minutes and 12 seconds. Oxford 21, Cambridge 17

Steve Fairbairn rowed at 6 for Cambridge. Both boats had problems finalising their crews.

The day was fine and sunny with a north west breeze. Cambridge won the toss, chose Middlesex

and took an initial lead. Oxford however came level in about one minute and Cambridge looked ragged.

Oxford slowly increased their lead and markedly so in the rougher water of the Chiswick Reach.

Oxford won by 20 seconds (7 lengths).

Bow 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stroke Cox |

OXFORD 1882 G C Bourne, 10.13 R S de Haviland, 11. 1½ G S Fort, 12. 3½ A R Paterson, 12.12 R S Kindersley, 13. 4½ E Buck, 12. 0 D E Brown, 12. 6 A H Higgins, 9. 6½ E H Lyon, 7.12 |

Bow 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stroke Cox |

CAMBRIDGE 1882 Ll R Jones, 11. 1 A M Hutchinson, 12. 1½ J C Fellowes, 12. 7 P W Atkin, 12. 1½ E Lambert, 11.12 S Fairbairn, 13. 0 C W Moore, 11. 7 S P Smith, 11. 1 P L Hunt, 7. 5 |

Oxford 2, Reginald Saumarez de Havilland, "Havvy"

Eton Coach in 1901

40: 1883, Thursday, 15th March

In 1883 OXFORD WON by 3½ lengths. Time 21 minutes and 18 seconds. Oxford 22, Cambridge 17

Despite having Steve Fairbairn in the boat Cambridge were not convinced by his style and imported

an Oxford coach. They had difficulty finding a stroke due to illness. And their boat was not suited

to so heavy a crew.

Oxford also had trouble with finding a stroke, and also had boat problems, solved by a new

boat with a fin.

The Start was a fiasco -

At exactly twenty minutes to six, just as the gas lights on Putney Bridge had been lit

and the mists of evening seemed to be settling down for good on the river,

both crews were in their places ready for the signal to "Go".

Oxford, having won the toss, on the Surrey side.

Unfortunately, the start, for some reason or other was by no means a perfect one.

The reason was given in a letter from Dr Bourne [rowing at Bow for Oxford] -

We were started, as usual, by old Searle

[Edward Searle who had started every Boat Race since 1840, or possibly earlier]

who was in a moored skiff between the two crews. He was old and his voice feeble.

He warned us that he would ask once Are you ready? and then start us by dropping his handkerchief.

He gave Are you ready?. A long pause his handkerchief fluttered in the breeze and West

[the Oxford stroke] was off.

We [Oxford] rowed two or three strokes,

saw that Cambridge were not rowing and most of us stopped rowing.

Cambridge started, came alongside and their bow oar also stopped rowing and we looked at each other,

wondering what was to happen. Then we realised that the race was inevitably started

and that the steamers had caste their moorings and were bearing down on us.

Then we set to work.

Every cox soon learns - there is no future in making polite hesitant suggestions to oarsmen -

orders need to be incisive, short, and clear. The starting ritual needs to be the same. And of course

it is a ritual. It needs to be totally predictable - so that when the words are blown away by a high

wind the instruction to start is still effective. So it needs to be firmly established beforehand

and never varied. In this case even Dr Bourne can't tell us if this was a false start.

At any rate (in Oxford's case 42) the race eventually got under way with a slight lead to Oxford.

A snowstorm then started and the wind rose so that conditions became rough.

The snow now came down in a dense shower and what with a little difficulty between the Oxford and the Press steamers, those members of the Fourth Estate who were on board the latter saw no more of the race.

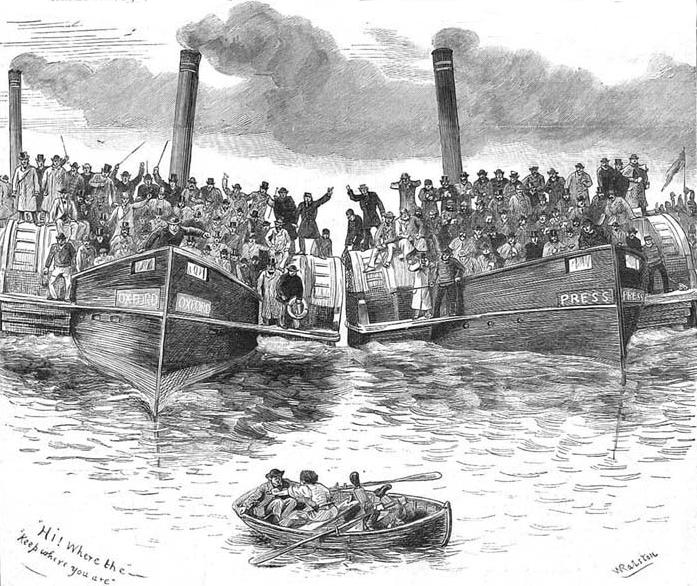

'A little difficulty between the Oxford and Press steamers' ... 1883

Oxford led by a length at Hammersmith Bridge, by three lengths at Chiswick Steps, by four lengths at Barnes Bridge and by three and a half lengths at the finish.

Bow 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stroke Cox |

OXFORD 1883 G C Bourne, 10.11½ R S de Havilland, 11. 4 G S Fort, 12. 0 E L Puxley, 12. 6½ D H McLean, 13. 2½ A R Paterson, 13. 1½ G Q Roberts, 11. 1½ L R West, 11. 0 E H Lyon, 8. 1 |

Bow 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stroke Cox |

CAMBRIDGE 1883 R C M G Gridley, 10.7 F W Fox, 12. 2 C W Moore, 11.13 P W Atkin, 12. 1 F E Churchill, 13. 4 S Swann, 12.12 S Fairbairn, 13. 4 F C Meyrick, 11. 7 P L Hunt, 8. 1 |

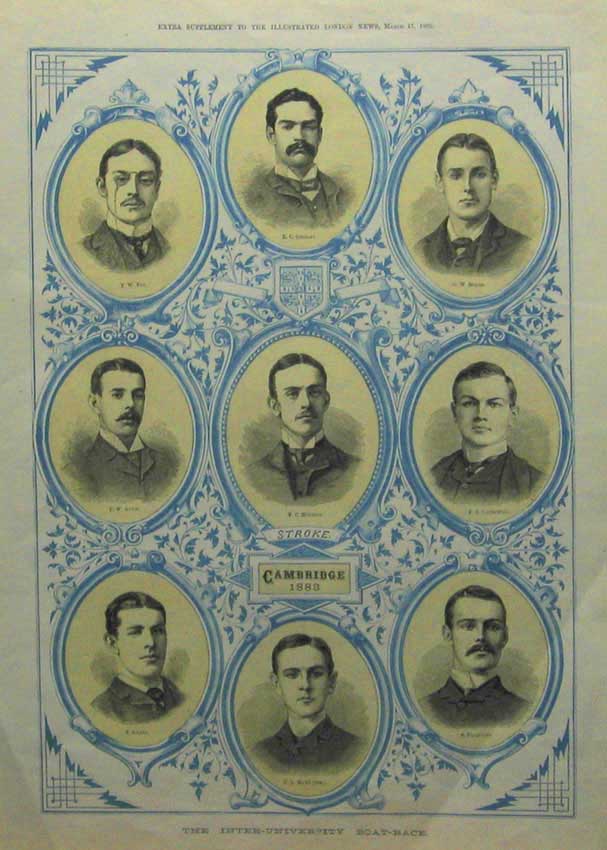

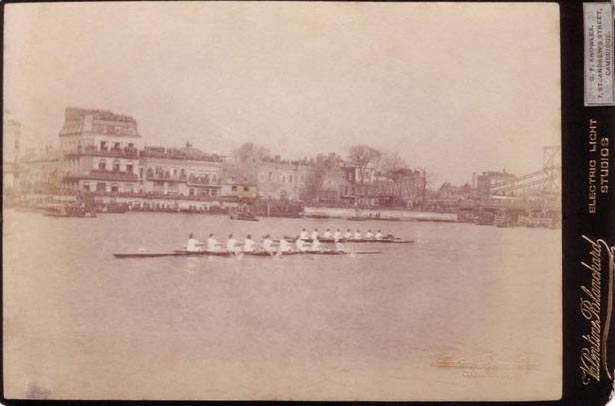

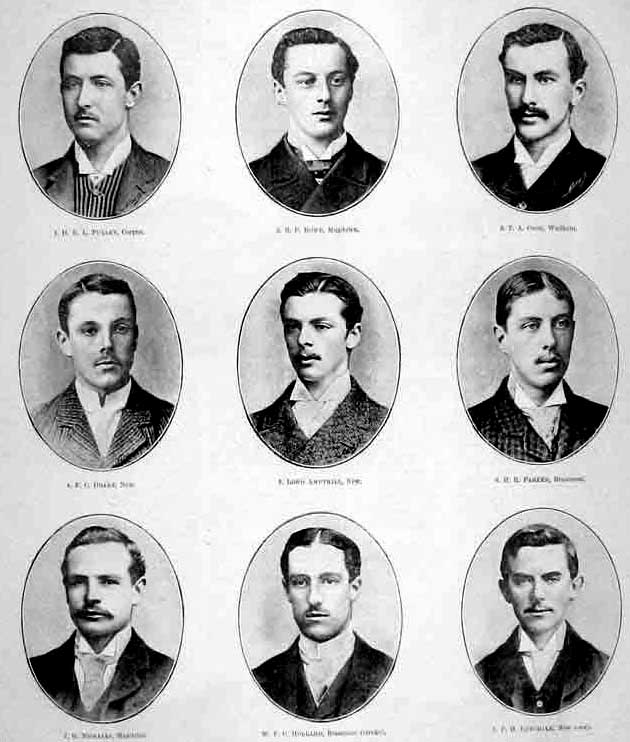

Cambridge Crew 1883 -

Cambridge Crew 1883

Cambridge Crew 1883

Steve Fairbairn, (Cambridge 7) who was so influential in Cambridge rowing, wrote the following poem, to enshrine his style -

THE OARSMAN'S SONG

"The willowy sway of the hands away"

And the water boiling aft,

The elastic spring, the steely fling

That drives the flying craft.

The steely spring and the musical ring

Of the blade with the biting grip,

The stretching draw of the bending oar

That rounds the turn with a whip.

The lazy float that controls the boat

And makes the swing quite true,

And gives that rest that the oarsman blest

As he drives the blade right through.

All through the swing he hears the boat sing

As she glides on her flying track,

And he gathers aft to strike the craft

With a ringing bell note crack.

From stretcher to oar with drive and draw,

He speeds the boat along.

All whalebone and steel and a willowy feel,

That is the oarsman's song.

Modern oars persons will immediately notice that the catch (start of the stroke in the water)

was a different matter before the modern blade shapes came in. When coaches attempted to teach me

they explained that the beginning had to be hit - "the ringing bell note crack" - so that the blade

had a solid lump of compressed water to work against - and that that water had to be kept compressed thoughout

the stroke, otherwise the blade would wash out (Oh the shame of it!)

But modern blades are different. On their own without doing anything, if they smell water they lock

onto it. The sharp hit at the start of the stroke is no longer necessary - and indeed the jerk which

it caused can be eliminated. Presumably with the greater blade area the pressure per square inch

for a given effort is much lower. Modern rowers simply place the blade where it is needed and smoothly accelerate

it through the stroke (at least that is the theory!)

And here is Steve Fairbairn 50 years later with his bust and sculptor George Drinkwater -

Steve Fairbairn and George Drinkwater

It is on the title page of 'CHATS ON ROWING' by Steve Fairbairn. He says -

George Drinkwater the famous artist, sculptor, oarsman, coach and rowing scribe,

doing my bust which is the trophy for the head of the river race.

When I began sitting for this I had no belief in the possible result.

But one day I saw George had produced a real likeness of myself expressing the thought I always have on rowing;

"Friends, Romans, Countrymen, lend me your ears".

Good luck George.

The Fairbairn Races at Cambridge are still run by his college (Jesus).

George Drinkwater wrote "The Boat Race" (1829 - 1939). He rowed Bow for Oxford in 1902, and 7 in 1903.

He died in an air raid in the second World War.

27: 1884, Monday, 7th April

In 1884 CAMBRIDGE WON by 2½ lengths. Time 21 minutes and 39 seconds. Oxford 22, Cambridge 18

The race was to have been held on Saturday, 5th April, but was postponed due to the funeral

of Queen Victoria's youngest son, Leopold, Duke of Albany, who died at the age of 31.

Cambridge selection and training went well whilst Oxford found life difficult.

Oxford won the toss and chose Surrey. The wind that had been very strong abated just before the

race but it became very shifty as the Contemporary report reads, veering between

north and south-west but the surface of the water was wonderfully smooth with a sluggish tide.

The start was another difficult one -

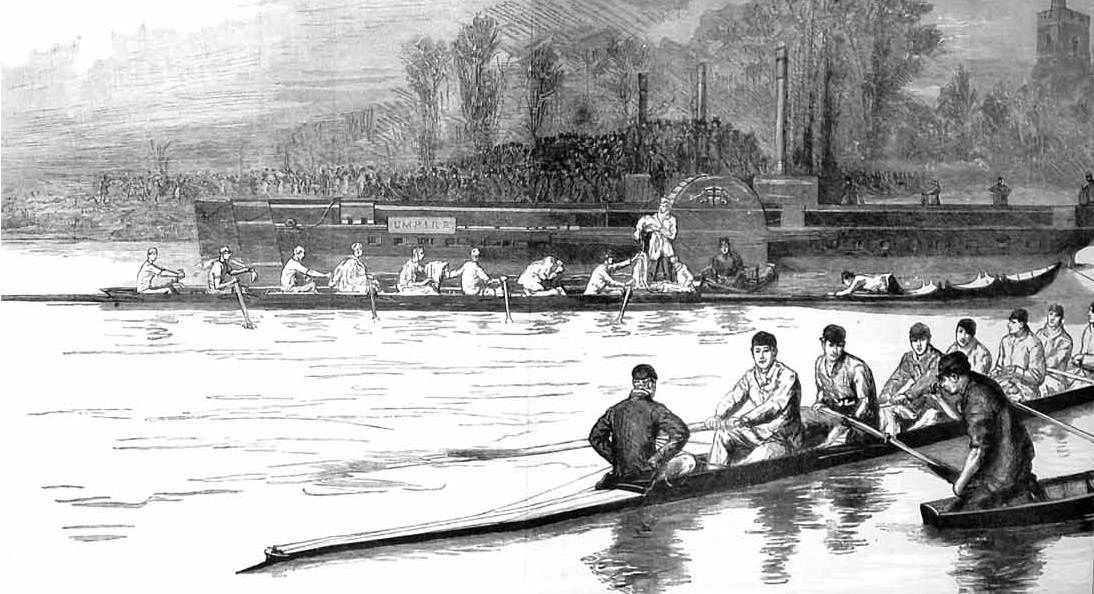

At the start, 1884

Time after time gusts of wind driving the Lorna Doone [the umpires launch] over towards

the Oxford station and even when the crews took up their positions, the Oxonians were continually

hampered by the launch driving over nearly on the top of them.

At length the umpire asked "are you ready?" and in the anticipation of the word "Go"

the Cantabs took a grip of the water. Just then, however, a violent gust had once more blown

the launch Surreywards and the Oxford oarsmen could not get under weigh.

Eventually they started and Cambridge went into the lead, though Oxford was pushing all along the

Fulham Wall. At Craven steps Cambridge led by almost one length,

at the Crabtree Cambridge led by over a length,

at Hammersmith Bridge they were 1¼ lengths ahead.Oxford made a determined effort to move up

and had some success but Cambridge responded and led by 1½ lengths at Chiswick steps.

By Barnes Bridge they were 3 lengths ahead and Oxford had no answer.

Oxford striving manfully behind Cambridge in sight of the finish, 1884

Cambridge won by 2½ lengths.

Cambridge colours hoisted to celebrate victory, 1884

Bow 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stroke Cox |

OXFORD 1884 A G Shortt, 11. 2 L Stock, 11. 0 C R Carter, 12.10 P W Taylor, 13. 1 D H McLean, 12.11½ A R Paterson, 13. 4 W C Blandy, 10.13 W D B Curry, 10. 4 F J Humphreys, 7. 6 |

Bow 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stroke Cox |

CAMBRIDGE 1884 R C M G Gridley, 10. 6 G H Eyre, 11. 3½ F Straker, 12. 2 S Swann, 13. 3 F E Churchill, 13. 2½ E W Haig, 11. 6¾ C W Moore, 11.12¾ F I Pitman, 11.11½ C E Tyndale-Biscoe, 8. 2 |

27: 1885, Saturday, 6th April

In 1885 OXFORD WON by 2½ lengths. Time 21 minutes and 36 seconds. Oxford 23, Cambridge 18

Oxford were on average half a stone heavier and their training went much better than that of Cambridge who had considerable

selection problems due to illness.

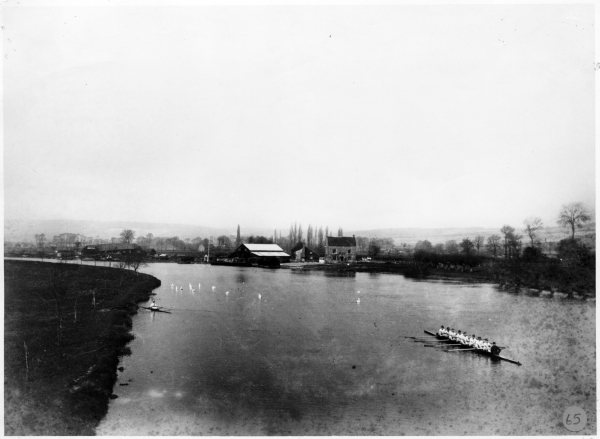

The Oxford eight training on the river Thames seen from the Railway Bridge, Bourne End, 1885

Oxford were staying at Abney House.

The old Hammersmith Suspension Bridge of 1827 had to be replaced. It may even have been the boat race that had damaged it!

In the 1870s it was found that a crowd of between 11,000 and 12,000 people had tried to watch the boat race from it and they

may well have overloaded it.

To replace it the first move was to install a temporary wooden bridge.

However this caused problems for the boat race because the main arch of the temporary bridge

was only about 50 feet wide which would somewhat inconvenience two

eights (they could do it in theory if they allowed clearances of 18 inches between bridge and oar tip and between oar tip and oar tip.

But this was thought to be asking too much of the coxes on the tideway - though most experienced

Oxbridge coxes, accustomed to the bumps on a winding river would think nothing of eighteen inches!

In 1886 they managed it with the boats level ...)

It was therefore decided that the crew which were on the Surrey station should go through the Surrey arch while the other crew

should use the main arch. This gave a very great advantage to the winner of the toss,

choosing the Surrey station, for not only would the total distance travelled be substantially less, but the Middlesex crew would need

to make two fairly tight turns to negotiate the main arch causing rudder drag. There were various estimates of the

benefit to the winner of the toss, but the popular view was about 1½ to perhaps as much as 2 lengths.

[That is the accepted view - but to my mind it all depends on the tide. A good tidal stream would favour going

relatively wide at Hammersmith Bridge.]

On boat race day the weather was good with a NNW breeze.

Oxford won the toss and (with the Hammersmith Bridge situation) obviously chose the Surrey station.

Cambridge made a good start and moved into a ½ length lead. Oxford soon came back and it is said that Cambridge

tried to push them inshore out of the main stream of the tide as they came up level.

Oxford had to jinx round a moored boat but then

a few feet ahead lined up for the Surrey Arch at Hammersmith Bridge.

Cambridge had to steer out to get through the Middlesex arch.

At this point Oxford then had nearly two lengths lead.

Suddenly the Oxford boat lurched and it looked to spectators as if a crab had been caught.

They recovered, and the fact was that the Oxford 3, P.W.Taylor, had put his shoulder out of joint, but being used to the problem

had managed to get it back into its socket and rowed on in great pain!

At Chiswick Steps Oxford led by over four lengths.

Despite difficulties avoiding a skiff Oxford won by 2½ lengths.

Bow 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stroke Cox |

OXFORD 1885 W S Unwin, 10.10½ J S Clemens, 11. 9 P W Taylor, 13. 6½ C R Carter, 13. 2 H McLean, 12.12 F O Wethered, 12. 6½ D H McLean, 13. 1½ H Girdlestone, 12. 7 F J Humphreys, 8. 2 |

Bow 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stroke Cox |

CAMBRIDGE 1885 N P Symonds, 10. 8 W K Hardacre, 10. 9 W H W Perrott, 12. 1 S Swann, 13. 4 F E Churchill, 13. 3 E W Haig, 11. 8 R H Coke, 12. 4 F I Pitman, 11.13 G Wilson, 7.11 |

Replacement of Putney Bridge

43: 1886, Saturday, 3rd April

In 1886 CAMBRIDGE WON by 2/3 length. Time 22 minutes and 4 seconds. Oxford 23, Cambridge 19

Oxford had a good experienced crew, but Cambridge had Steve Fairbairn and Muttlebury.

The temporary bridge at Hammersmith was still in place but after the 1885 race it was agreed

to try to use the one 50 foot wide arch for both boats. However since the general opinion seemed to be

that the chances of threading it with the boats level was low, it was agreed that if there was a clash

the race would be restarted above the bridge, and in that case a second finish above the usual finish

would be used. To rub in the general opinion about coxes the umpire's launch would carry a spare full

set of blades for each boat.

Thus encouraged the coxes set to work.

Oxford won the toss and chose Surrey. Cambridge led off the start and were about ½ length up.

But then Oxford came back and the lead changed hands. Cambridge then came back on them -

and (who would believe it?) the crews were level as they came to the narrow arch at Hammersmith!

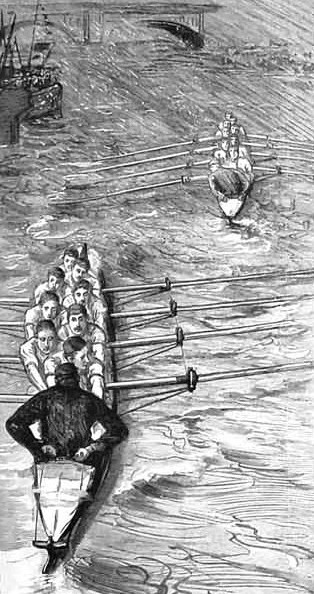

Both coxes managed it perfectly. The situation was sketched -

The two Boat Race eights threading the Hammersmith Bridge, 1886

Oxford now had the smoother water and moved out to a length lead at Chiswick steps and to

two lengths at Barnes Bridge. Most boat races would have been over by then!

But Cambridge performed heroically, raising the rating to forty for three minutes.

Oxford on the Surrey station had naturally taken Cambridge's water for the last bend to the finish

and as Cambridge caught them they were forced to move back to their own side. Cambridge came past

and won by two thirds of a length.

Since oarsmen face backwards there is a considerable advantage in being in front and being able

to see your opponents and counter any move they make. If they begin to catch up you can respond in good time.

Meanwhile your cox can steer so that the four 'puddles' - the fairly large whirlpools made by the blades -

arrive precisely where they will do the most good - under the blade tips of the boat behind you, or possibly on their bows.

In the days of large rudders (and of course particularly on the more bendy rivers of Oxbridge) it was

also possible to 'wash off' opponents by arranging for a strong rudder movement to send a wave at them.

Altogether it is better to be in front!*

[ * statement of the obvious! ]

To be behind means not only are you losing, and facing defeat, but also that you are blind. When the

opposition is two lengths ahead they might as well be six lengths away.

It is at that moment that all

those bitter winter training sessions come into their own. Instead of lamenting your fate you do what

you were trained to do - you sit up and go through the litany that you have learned -

the catches [ more important with the narrow blades of earlier days - the water had to be compressed

and held compressed otherwise the blade just washed out ] - the drive with the legs - the finishes -

the hands away - the controlled approach to front stops. Never mind that a million people are watching

you - are you remembering all those tiny details in which you have been coached? Is your timing perfect? And if you

get that right, and the boat in front does not, and you are not yet rowed out, then miraculously there they are beside you again -

and just maybe ...

R C Lehmann in "The Complete Oarsman" named three Boat Races WON AFTER BARNES BRIDGE

The Three University Boat Races won after Barnes Bridge, 1886, 1896, 1901

IN one sense of course every University boat-race is won after

Barnes, for the judges' flag does not fall until the Ship at

Mortlake has been passed I use my heading, however, in a

peculiar sense, well known to rowing men, and I indicate by

it a race in which a crew that had fallen behind and was

apparently defeated at Barnes Bridge has made up its lee

way from that point and has passed the post first.

It is very generally supposed that the crew which passes first through

Barnes Bridge must win. The annals of the University boatrace

supply three exceptions to this rule. The first of these

occurred in 1886.

There had been four Oxford victories in succession from

1880 to 1883 inclusive. In 1884 Cambridge, stroked for the

first time by F. I. Pitman, had won, but they had been

defeated again in 1885.

In 1886 Pitman was in his old place. Neither of the crews met with any serious misfortune

during practice, though Oxford had considerable trouble

in finding a boat that would carry them properly. Finally

the London Rowing Club lent them a boat, and in this they

rowed the race. She was a large and roomy boat, and had great

advantage of carrying her crew well in rough water. The

Cambridge boat, on the other hand, was rather small for the

tideway. In smooth water she travelled with a surprising

pace, and did full justice to the rowing of the crew, but for a

stormy sea she was cut down too fine.

On the day of the race under the conditions of weather

then prevailing, the wind was more or less astern of the crews

to Hammersmith, and the water up to that point was perfectly

smooth. After the crews had rounded the Hammersmith

bend they met the full force of the wind, and the water,

except just under the lee of the Surrey shore, was terribly

rough. Oxford had the Surrey station, Cambridge the

Middlesex.

Both crews started very fast. Travelling on a smooth

surface, and with no wind to impede them, they raced along

neck and neck to the old Soap Works at a stroke that rarely

fell below 38 to the minute.

Hammersmith Bridge was then undergoing repairs, and the scaffolding had left a space

through which two crews could just manage to pass abreast

without a collision. At this point the two crews were abreast,

and they went under the bridge dead level, a very remarkable

feat of steersmanship on the part of both coxswains.

Soon after Hammersmith Bridge, as I said, the crews had to meet

the full force of the wind, and the rate of stroke in both

necessarily began to drop, first to 35, then to 33, then to 32

and less. Oxford had the more sheltered station, and in any

case their boat made better weather of it, while Cambridge

were pounding along against the gusts and the waves that

every now and then, as I remember, broke over the back of

their bow man.

Oxford were drawing away, and foot by foot

were adding to their lead. As the crews neared Barnes

Bridge the water became smoother, and Cambridge began to

quicken their stroke, at first without much effect.

At Barnes Bridge Oxford were clear, nay, there was nearly

a length of daylight between the boats. The Cambridge men

on the following steamers hung their heads in gloomy silence ;

the Oxford shouts rose louder and louder, and more and more

jubilant, for victory with such a lead and only four minutes left

for racing was an absolute certainty.

And so the Oxford crew, having taken the Cambridge water on the Middlesex

side, went sailing gaily along towards Mortlake unconscious

of their doom. As the Cambridge crew, however, passed

under the crowded railway bridge, Pitman nerved himself for

a desperate effort. He picked up his stroke, and, gallantly

backed up by his men, rowed twenty-one in the first half-

minute and forty in the full minute.

The gap began to close as though by magic; in a few more strokes Cambridge would

bump their rivals. The Oxford coxswain became conscious

of his danger. He ought to have given way gradually so as

to get back to his own water.

Instead of this he pulled his

left-hand rudder-string hard, and brought his boat almost

sheer athwart the tide. By the time he had straightened her

Cambridge were nearly level, and from this point, rowing with

renewed life, and conscious after all their dismal toil that victory

was within their grasp, they drew away from the shattered

Oxonians, and won the race by two-thirds of a length.

Bow 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stroke Cox |

OXFORD 1886 W S Unwin, 10.11 L S R Byrne, 11.11½ W St L Robertson, 11. 7½ C R Carter, 13. 0½ H McLean, 12.12 F O Wethered,12. 6 D H McLean, 13. 0 H Girdlestone, 12. 9¼ W E Maynard, 7.12 |

Bow 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stroke Cox |

CAMBRIDGE 1886 C J Bristowe, 10. 8½ N P Symonds, 10.10 J Walmsley, 12. 1 A D Flower, 12. 8½ S Fairbairn, 13. 9 S D Muttlebury, 13. 3 C Barclay, 11. 3 F I Pitman, 11.10½ G H Baker, 6. 9 |

Joseph Ashby-Sterry published 'The Lazy Minstrel' in 1886 and included the following -

THE IMPARTIAL - A BOAT-RACE SKETCH.

IN sorrow and joy she has seen the beginning -

Her lightness of spirit half dashed by the "blues" -

With cheers in her heart for the crew who are winning,

While tears fill her eyes for those fated to lose.

If you'll narrowly watch, 'mid the noise and contention,

You'll note, as her Arab paws proudly the dust,

A deftly-twined bouquet of speedwell and gentian

Beneath her white collar half carelessly thrust !

The tint of a night in the still summer weather

Her tight-fitting habit just serves to unfold,

While delicate cuffs are scarce fastened together

By dainty-wrought fetters of turquoise and gold.

Ah ! climax of sweet, girlish, neutral devices -

What smiles for the winners, for losers what sighs !

She has twined her fair hair with the colours of Isis,

While those of the Cam glitter bright in her eyes !

44: 1887, Saturday, 26th March

In 1887 CAMBRIDGE WON by 2½ lengths. Time 20 minutes and 52 seconds. Oxford 23, Cambridge 20

Finally the temporary bridge at Hammersmith had gone and in its place was the brand new Hammersmith

Suspension Bridge as we know it today. 688 feet long, 33 feet wide.

Two river-towers of wrought iron clad in highly ornamental cast iron support steel

suspension chains from which the narrow carriageway is hung.

The footways are cantilevered out from the main structure.

Engineer: Joseph Bazalgette. Contractor: Messrs Dixon, Appleby and Thorne

1890: Current Hammersmith Bridge, Henry Taunt -

Current Hammersmith Bridge, Henry Taunt, 1890

© Oxfordshire County Council Photographic Archive; HT00339

[ NB The first bridge had the very square stone flat topped pillars,

and the iron more ornate pointed supports belong to the second (and current) suspension bridge. ]

And here is the race in 1887 with Hammersmith Bridge in the far right (still with temporary staging under the approach section)

Boat Race at Hammersmith Bridge, 1887

Copyright David Rice

1887 was the golden year of Cambridge rowing -

every final at Henley Royal Regatta in 1887 was won by a Cambridge contestant:

Trinity Hall won the Grand, the Ladies, the Thames, the Stewards and the Visitors!

Pembroke won the Wyfolds; Third Trinity won the Goblets; and Gardner of Emmanuel the Diamonds.

120 years later (and before getting into boat race history) I had heard of three of the 1887

boat race crew!

However one of those, Guy Nickalls, was in the Oxford Boat, albeit at only three weeks notice.

The other two were the mighty Muttle - Muttlebury (see 1890)

and the legendary Steve Fairbairn

in whose race ('the Fairbairns' at Cambridge) I have rowed and coxed and coached in a humble capacity

longer than I care to remember (rowing in 1965 and coxing most recently in 2013).

The weather and tide were good, though a strong west wind produced problems in the last part of the course.

Cambridge won the toss and chose Surrey.

Cambridge started well and opened up a lead of a few feet.

But then Oxford responded and held them there.

Cambridge then began to open a lead of two lengths at the new Hammersmith Suspension Bridge.

In the rougher water of Chiswick Reach Cambridge in the shelter of the Surrey bank suffered less than

Oxford and opened their lead to three lengths. As Oxford came back into the shelter of the next bend

they caught up a little but it was still nearly three lengths at Barnes Bridge.

Cambridge won from two lengths down at Barnes Bridge in 1886 - but three lengths was asking

a bit much. And when the blade of Oxford's 7, D.H.McLean, broke off cleanly at the button

and he was left holding just the handle, Oxford were lucky to finish - let alone catch up.

Cambridge won by 2½ lengths.

Guy Nickalls, Oxford 2, in "Life's a pudding" wrote:

There was no doubt over the whole course that we were the faster crew, but Frank Wethered damned the whole outfit.

An hour before the race we rowed two minutes at 40 from the start.

Dissatisfied with the row, which was certainly scrambled, we were taken back to the start and made to row as hard as we could back to the Mile Post.

When we started the race an hour later I was dead to the world and stale, as were all the new blues.

Cambridge led us a length under Barnes Bridge and Titherington was holding his spurt.

We were on Middlesex shore, and, out of the corner of my eye, I could see the Cambridge cox bobbing back to us at every stroke.

Titherington began his spurt; back they came to us.

I was opposite their stroke; we knew the race must be ours and Holland yelled: Its all right, weve got em!

Then, Ducker McLean broke his oar off short at the button.

With the station in our favour and him out of the boat we could have won even then, but Ducker funked the oncoming penny steamers and,

instead of jumping overboard as he should have done, we had to lug his now useless body along, to lose the finish.

That was disappointing. Titherington was a fine stroke.

R C Lehmann in "The Complete Oarsman" was more charitable -

Cambridge had beaten Oxford in the spring by 2 1/2 lengths, but the race had not been a very satisfactory one, for the Oxford No. 7, D. H. McLean, had managed to break his oar at a critical moment when Oxford were making a spurt and were gaining on Cambridge. This time the oar was unquestionably broken into two pieces. I saw the blade portion floating in the water as we came along in the steamer, which had been left far behind, and when we once more caught sight of the crews, we could see that McLean was swinging and recovering as best he could without an oar.

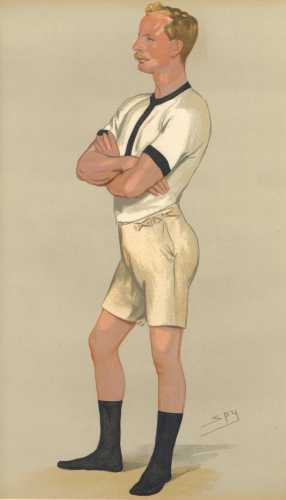

Douglas Hamilton McLean |

Guy Nickalls |

Bow 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stroke Cox |

OXFORD 1887 W F C Holland, 10. 9 G Nickalls, 12. 1 S G Williams, 12. 5 H R Parker, 13. 3 H McLean, 12. 8½ F O Wethered, 12. 5 D H McLean, 12. 9 A F Titherington, 12. 2 L J Clarke, 7. 9 |

Bow 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stroke Cox |

CAMBRIDGE 1887 R McKenna, 10. 7 C T Barclay, 11. 1 P Landale, 12. 0½ J R Orford, 13. 0 S Fairbairn, 13. 5½ S D Muttlebury, 13. 6½ C Barclay, 11. 8 C Bristowe, 10. 7½ G H Baker, 7. 1 |

Cambridge Bow, Reginald McKenna (politician in 1906)

45: 1888, Saturday, 24th March

In 1888 CAMBRIDGE WON by 7 lengths. Time 20 minutes and 48 seconds. Oxford 23, Cambridge 21

In January Oxford lost Hector McLean, their 1887 President, to typhoid fever.

Muttlebury was president at Cambridge.

The winter was difficult for training though conditions were almost ideal on race day.

Cambridge started well -

Both crews struck the water together, but the effect was very different. Cambridge seemed as if they had imparted life into the boat and she bounded away like a greyhound, leaving the Oxonians as if they were sitting still.

And that is the way it stayed with Cambridge moving steadily away until the last 3 minutes when with a seven length lead they eased down and maintained the seven lengths to the finish.

Bow 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stroke Cox |

OXFORD 1880 W F C Holland, 11. 0 A P Parker, 11.11 M E Bradford, 11. 9 S R Fothergill, 12.10 H Cross, 13. 0½ H R Parker, 13. 5 G Nickalls, 12. 4 L Frere, 10. 0½ A H Stewart, 7.13½ |

Bow 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stroke Cox |

CAMBRIDGE 1880 R H Symonds-Tayler, 10. 7 L Hannen, 11. 3 R H P Orde, 11. 7 C B P Bell, 12.13½ S D Muttlebury, 13. 7 P Landale, 12. 4 F H Maugham, 11. 5 J C Gardner, 11. 7 J R Roxburgh, 8. 2 |

46: 1889, Saturday, 6th April

In 1889 CAMBRIDGE WON by 3 lengths. Time 20 minutes and 14 seconds. Oxford 23, Cambridge 22

Cambridge most unusually boated the same crew as in 1888 (except the cox). Without selection pressure

their preparation was perhaps not as rigorous as it might have been.

Oxford had the opposite problem of having to start from scratch. Their training eventually went well

and they began that emphasis on the leg drive which all modern oarsmen now inherit.

The only weather comment was of a tremendous

sea raised by the wind above Barnes.

Cambridge were on Surrey, Oxford on Middlesex.

It was reported that both crews slightly anticipated the starting pistol.

Oxford had an early slight lead but Cambridge rapidly came back and then began forcing Oxford

over towards the Middlesex bank and out of the stream.

Cambridge led by ¼ length at the mile and 1½ length at Hammersmith Bridge.

Oxford steered to wide in Chiswick Reach and Cambridge opened their lead to 2 lengths.

It was 2½ lengths at Barnes Bridge.

The 'tremendous sea' above Barnes slowed both crews badly but Cambridge maintained the lead to

win by 3 lengths.

Bow 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stroke Cox |

OXFORD 1889 H E L Puxley, 11. 8½ R P P Rowe, 11. 9 T A Cook, 12. 2 F C Drake, 12.12 Lord Ampthill, 12.11 H R Parker, 13.11 G Nickalls, 12. 5 W F C Holland, 10.12 J P H Heywood-Lonsdale, 8. 2½ |

Bow 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stroke Cox |

CAMBRIDGE 1880 R H Symonds-Tayler, 10.10½ L Hannen, 11. 4 R H P Orde, 11.10 C B P Bell, 13. 1 S D Muttlebury, 13. 9 P Landale, 12. 8 F H Maugham, 11. 5½ J C Gardner, 11.10 T W Northmore, 7.13 |

Oxford 1889

Click for Hammersmith Bridge

Boat race in 1890s