London River Thames Boat Services

1811: The original bridge on this site was built by John Rennie and named Strand Bridge.

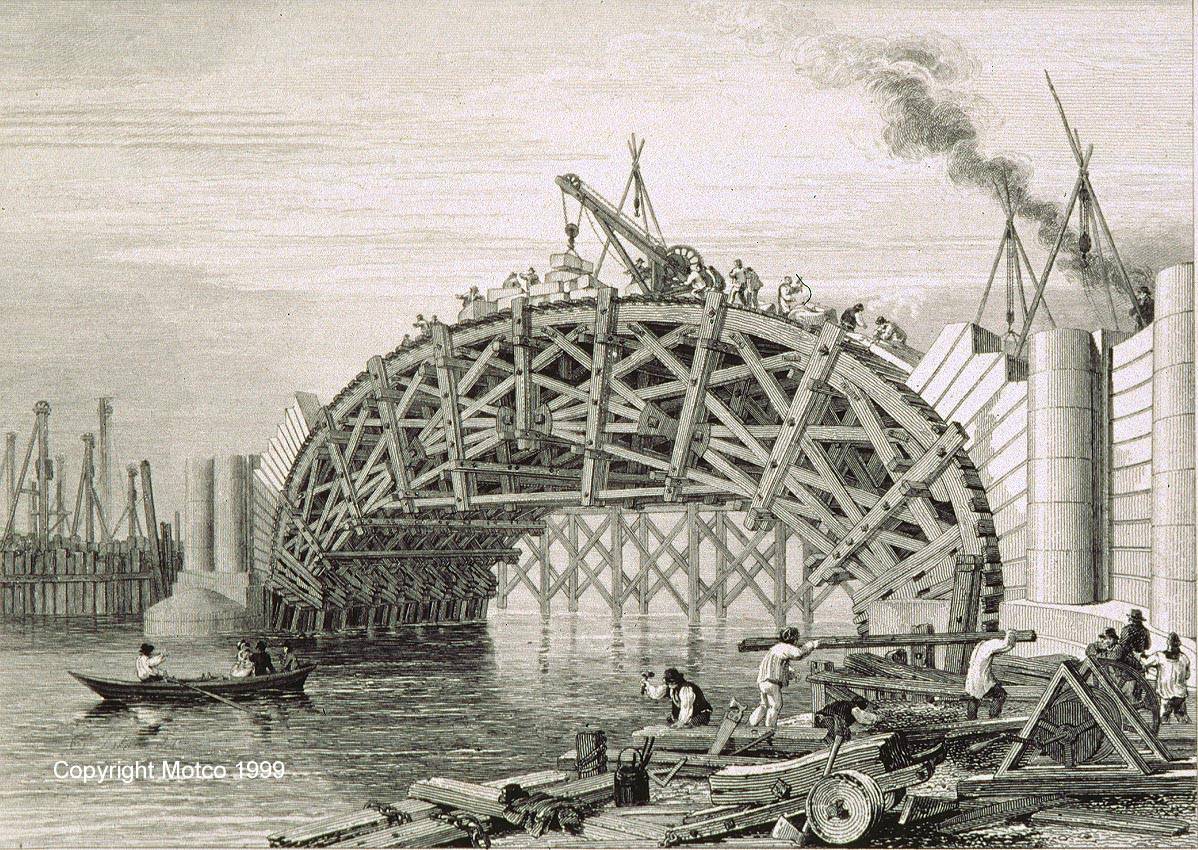

1815: Works of the Strand Bridge -

Works of the Strand Bridge (taken in the Year 1815).

Drawn by Edw. Blore. Engraved by George Cooke. Jan. 1, 1817

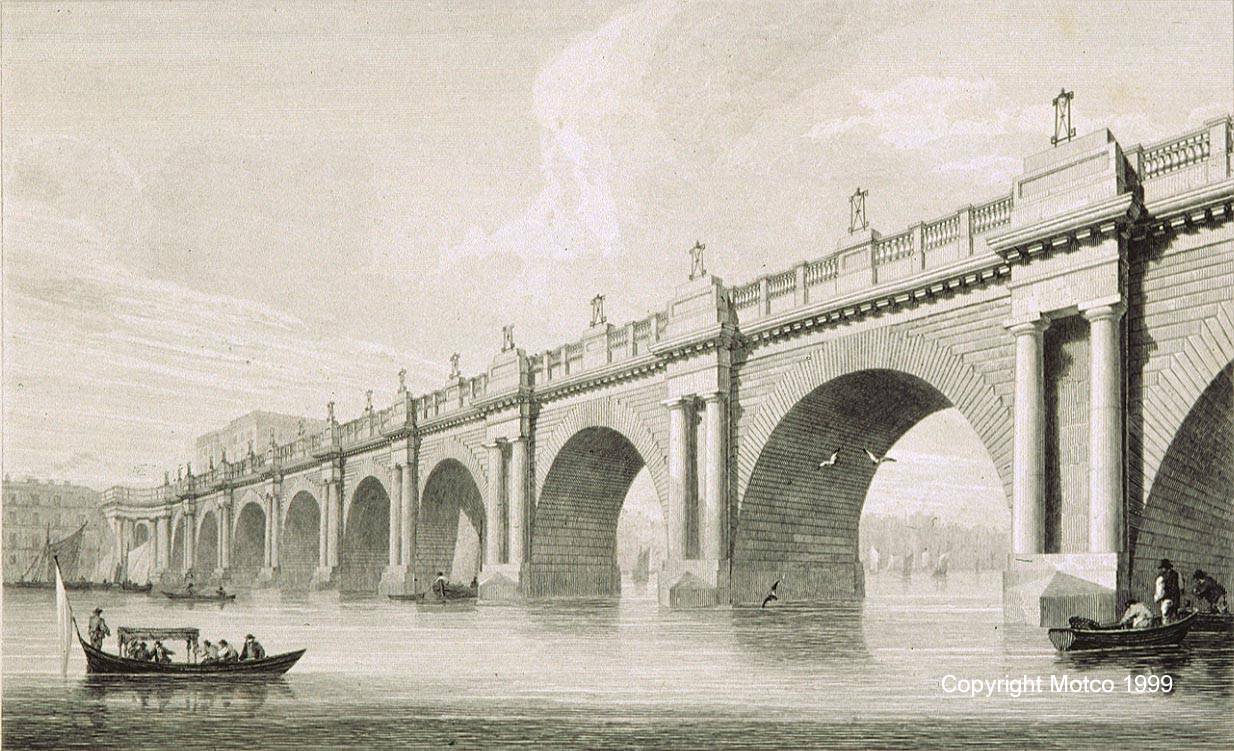

1814: The Strand Bridge (This next print purports to be earlier?)-

The Strand Bridge, New erecting by J. Rennie Esqr.

Drawn by E. Blore. Engraved by George Cooke. March 31, 1814.

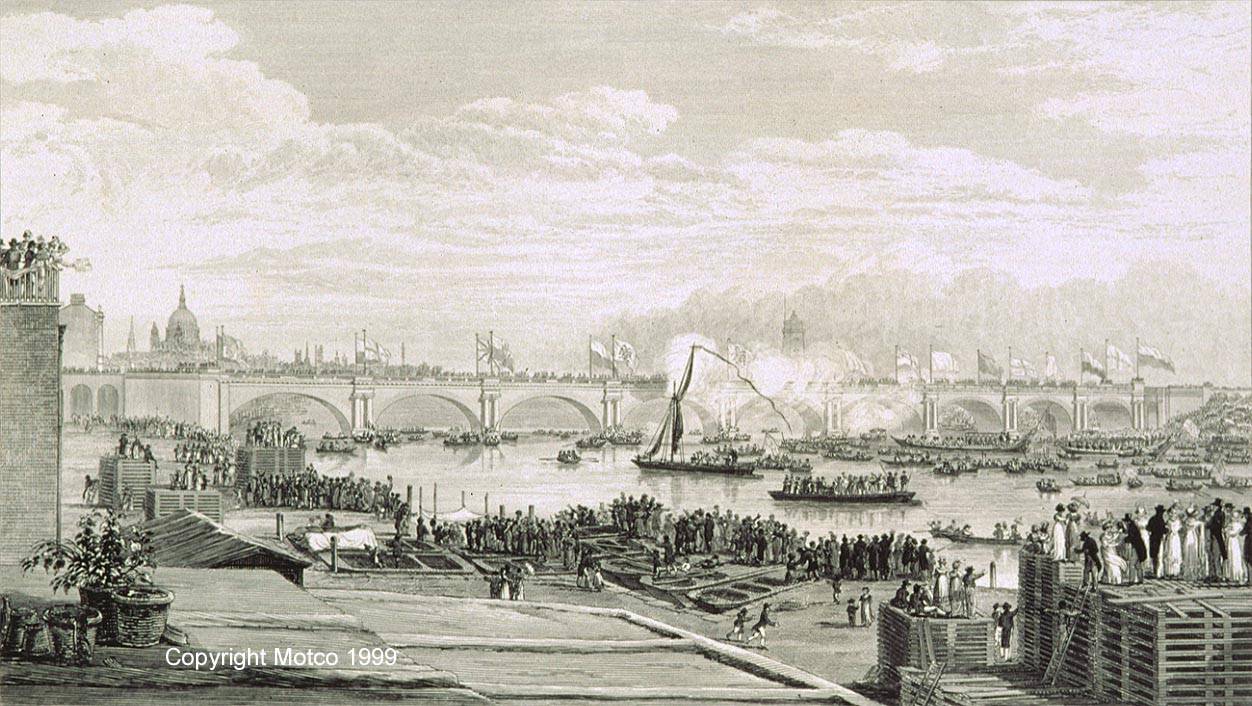

1817: Opening of Waterloo Bridge, June 15

on the second anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo

by the Prince Regent accompanied by the Duke

of Wellington and many of the staff officers who had been at the battle.

From The Times -

This noble structure was opened yesterday for the public accommodation,

with as much splendour and dignity as it is possible to give to a ceremony of this description.

The bridge, as our readers know, was originally named "The Strand Bridge;"

but the natural and patriotic desire of commemorating, in the most noble public manner,

the ever-memorable victory of Waterloo, afforded a fine opportunity for changing its appellation

from that of the street merely into which it opens.

No mode of perpetuating great deeds by works of art is more consistent with good taste than

where such works combine, in a high degree, what is ornamental with what is useful.

Monuments of this kind have stronger claims on public respect than the costly construction of pillars,

obelisks, and towers. There are many instances of public works having received their names from

events honourable to the country in which they were erected. In late times, Buonaparte, who,

with all his vices, had a very shrewd insight into human nature, and the external means by which

it is worked upon, took advantage of this principle, not simply by his triumphal columns or arches

to the honour of Dessaix, of himself, and of his army; but also in giving to two new bridges

the names of Jena and Austerlitz, where he had gained two decisive victories. But those bridges,

however elegant and convenient, are but trifles in civil architecture and engineering when

compared with that which was opened yesterday; and the general appearance of which in its progress

attracted particularly the admiration of the Emperor of Russia on his visit to this country.

Opening of Waterloo Bridge on the 18th of June 1817

as seen from the Corner of Cecil Street in the Strand.

Drawn by R.R. Reinagle, A.R.A. Engraved by George Cooke. Augst 1, 1822.

from ILLUSTRATIONS OF PUBLIC BUILDINGS IN LONDON, Britton, Pugin & Leeds, 1832 -

In short, the accuracy of the whole execution seems to have vied with the beauty of the design,

and with the skill of the arrangement, to render the Bridge of Waterloo a monument,

of which the metropolis of the British empire will have abundant reason to be proud

for a long series of successive ages.

In closing these remarks on one of the most stupendous works of modern times,

we are induced to quote the observations of an enlightened French Engineer,

who visited this country for the purpose of examining our great engineering works,

and who received while here the most liberal treatment both from the Government

and from scientific men.

This he fully appreciated, and has honourably acknowledged it,

in a memoir addressed to the French Institute:

"If, from the incalculable effect of the revolutions which empires undergo,

the nations of a future age should demand one day what was formerly the New Sidon,

and what has become of the Tyre of the West, which covered with her vessels every sea?

the most of the edifices devoured by a destructive climate will no longer exist

to answer the curiosity of man by the voice of monuments;

but the Waterloo Bridge, built in the centre of the commercial world,

will exist, to tell the most remote generations,

'Here was a rich, industrious, and powerful city.'

The traveller, on beholding this superb monument, will suppose that some great prince wished,

by many years of labour, to consecrate for ever the glory of his life by this imposing structure.

But if tradition instruct the traveller that six years sufficed for the undertaking and finishing

of this work if he learns that an association of a number of private individuals

was rich enough to defray the expense of this colossal monument,

worthy of Sesostris and the Caesars he will admire still more the nation

in which similar undertakings could be the fruit of the efforts of a few obscure individuals,

lost in the crowd of industrious citizens."

1818: Waterloo Bridge -

Waterloo Bridge, 1818

1819: Elevation of one of the arches by John Rennie -

Elevation of one of the Arches of the Waterloo Bridge. 1819

Drawn by the late John Rennie Esqr., Engineer and Architect.

1820: Waterloo Bridge by Richard Havell -

Waterloo Bridge,Richard Havell, 1820

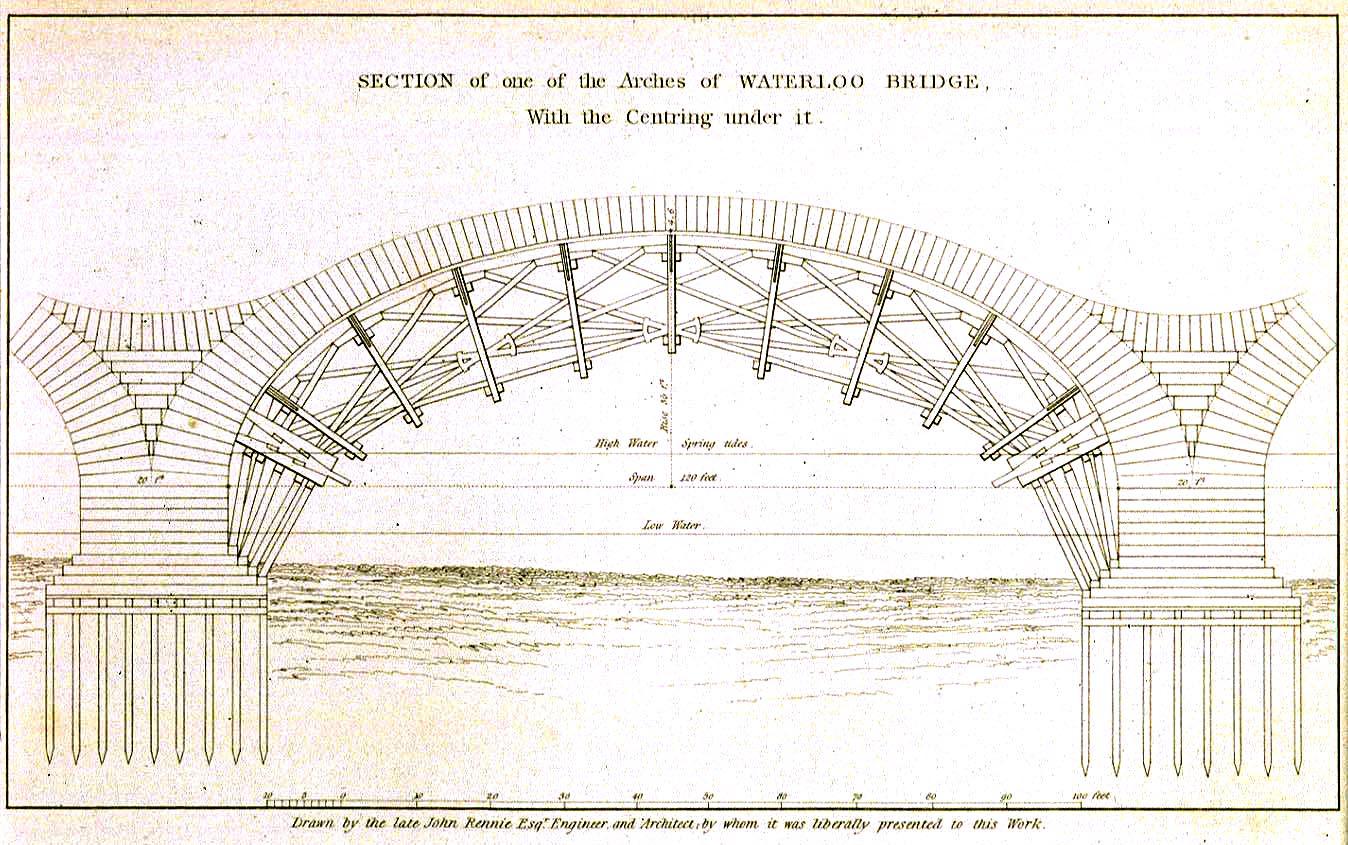

1821: Section of one of the arches by John Rennie -

Section of one of the Arches of the Waterloo Bridge with the Centring under it.

Drawn by the late John Rennie ... Novr. 1, 1821.

Waterloo Bridge 1827, Metropolitan Improvements

1827: The New Shot Mill near Waterloo Bridge, from Metropolitan Improvements, 1827 -

New Shot Mill near Waterloo Bridge 1827

... a new structure has been lately erected, called the patent shot manufactory. It is near one hundred and fifty feet high, about nineteen feet in diameter, and works half a ton of lead in an hour. It cost near six thousand pounds, but cannot be considered as an object ornamental to the river Thames.

1802: Letters from England By Manuel Alvarez Espriella, attributed to Robert Southey -

The first remarkable object below [Westminster] bridge is a tower constructed for making shot by a new process : the history of its invention is curious. About five-and-twenty years ago a Mr. Watts was engaged in this trade : his wife dreamt that she saw him making shot in a new manner, and related her dream to him : he thought it worth some attention, made the experiment, and obtained a patent for the invention, which he afterwards sold for ten thousand pounds.

1824: from The Steam Boat Companion -

That very lofty pile of brick building on our

left hand, where those columns of sable smoke

are flying before the breezes, is called

THE PATENT SHOT MANUFACTORY.

By the ingenuity and contrivance of the

proprietors, the sportsman is accommodated

with an article for his amusement, superior in

all respects to that manufactured on the former

principle. The spherical correctness, the purity,

and density of the shot, has been found

of high estimation by those who delight in the

terraflegiac art.

1828: Waterloo Bridge

Waterloo Bridge. W. Westall

A.R.A. delt. R.G. Reeve sculpt.

Published 1828 by R.Ackermann, 96 Strand, London. From West.

Antonio Canova (Italian Sculptor) said of Waterloo Bridge

The noblest in the world

1829: Painting of the Opening of Waterloo Bridge, Constable

Opening of Waterloo Bridge, 1829, Constable

1831: Four Years in Great Britain by Calvin Colton -

... a little before twelve o'clock.

The nearest and most direct road to my lodgings was across Waterloo Bridge ...

... soon found myself past the turnstile at the south end of the bridge.

Even in the daytime, as is well known to Londoners, this bridge is little frequented; in the evening less;

at the still and solemn hour of midnight, and near the shortest days of winter, scarcely at all.

The stars were concealed by smoke and clouds ; the lamps of that vast metropolis, beaming faintly up towards heaven, made the darkness visible ;

on the left, all along the shore towards Whitehall, the full glare of an occasional lamp down upon the glassy bosom of the Thames, threw up its sheet of scattered rays ;

the arched and regular lines of light across Westminster Bridge presented a beautiful vision ;

and down the river the lamps of Blackfriars' and Southwark bridges rivalled each other to give enchantment to the scene,

in the midst of the twinklings which darted from the confused mêlé of lights from either shore.

But the prettiest of all was the scene directly before me, created by the perspective of the two ranges of lamps on the sides of Waterloo Bridge,

drawing nearer together as the vista extended and approached the Strand.

This bridge is a dead level. I could see distinctly from one gate to the other, and not a human being was upon it.

I passed the turnstile on the right, after giving the keeper his penny, and hearing the tick of the clockwork, which

forces him to be honest. ...

As was natural, I kept the side to which I was thus introduced, and walked on at peace with myself, and I hope with Heaven,

admiring the stillness with which I was immediately surrounded at that dead hour of night, in the midst of such a world of human beings.

The distant rumbling of carriages, however, along the pavements of the streets, and that peculiar hum which accompanies it,

when heard at a little distance, and occasioned by the street-talk and night-rioting of so great a city, admonished me that the world were not all asleep.

But the twinkling lamps, everywhere to be seen, like the stars in an open sky, and the regular approaching lines immediately before me, were most attractive of all.

...

A poetic night time equivalent of Dorothy Wordsworth's diary entry on Westminster Bridge ... The only problem being that he then went on to describe a possible attempted robbery - and all that poetic feeling was just setting up his readers for the sudden attack - so be it - the world is probably like that - only I'm not going to add to it - you'll have to find how the story ends for yourself - here.

1835: The Parterre -

The name of the Waterloo bridge, as

well as its aspect, is sufficiently indicative

of its very recent date. Magnificent and

unique as it is, as a specimen of civil

architecture, yet to the eye, its flat, aqueduct-

looking line is less attractive than

either the stately elevation of the Westminster,

or the graceful sweep of Blackfriars.

Its name, too, is a sort of solecism, and, we cannot help thinking, an affectation,

not quite worthy of the solid and

lasting dignity of that metropolis which

acquired in the erection of this structure

one more noble feature in addition to the

many which it had already accumulated.

The names of all the other great bridges

of the capital, have grown out of their

respective localities ; so that their permanence

is not liable to be affected either

by political changes or by changes of

opinion. Those names are intimately

associated with the steady rise, the splendid

progress, and magnificent prospects

of the capital itself : their continuance is

not dependent on the judgment which

future generations, or even the present,

may form as to the degree of public

benefit that may have resulted from a

particular political or military achievement.

But even had British history had

time to pass its final verdict upon the

transactions in question, the taste would

still have been very questionable which

suggested the introducing of a name inseparably

associated with all the darkest

horrors of wholesale butchery, among

those of the Westminster bridge, &c.

which hold their steady, quiet place in

the mind, linked with ideas of cheerful

business, of peaceful pomp, and tranquil

pleasure.

And once more let me repeat,

that, of all cities that are or have been,

our own great capital may most fairly

claim the right, before all other localities

upon earth, to furnish names for her own

magnificent bridges.

1840: The Thames and its Tributaries, Charles Mackay -

... Waterloo Bridge, the finest of the many fine structures that span the bosom of the Thames within metropolitan limits.

Around its arches clings half the romance of modern London.

It is the English "Bridge of Sighs", the "Pons Asinorum", the "Lover's Leap", the "Arch of Suicide", and well deserves all these appellations.

Many a sad and too true tale might be told, the beginning and end of which would be "Waterloo Bridge".

It is a favourite spot for love assignations;

and a still more favourite spot for those who long to cast off the load of existence, and cannot wait, through sorrow, until the Almighty Giver takes away his gift.

Its comparative loneliness renders it convenient for both purposes.

The penny toll keeps off the inquisitive and unmannerly crowd;

and the foolish can love or the mad can die with less observation from the passers than they could find anywhere else so close to the heart of London.

To many a poor girl the assignation over one arch of Waterloo Bridge is but the prelude to the fatal leap from another.

Here they begin, and here they end, after a long course of intermediate crime and sorrow, the unhappy story of their loves.

Here, also, wary and practised courtezans lie in wait for the Asini, so abundant in London, and who justify its appellation of the Pons Asinorum.

Here fools become entrapped, and wise men too sometimes, the one losing their money, and the other their money and self-respect.

But, with all its vice, Waterloo Bridge is pre-eminently the "Bridge of Sorrow".

There is less of the ludicrous to be seen from its smooth highway than from almost any other in the metropolis.

The people of London continually hear of unhappy men and women who throw themselves from its arches,

and as often of the finding of bodies in the water, which may have lain there for weeks, no one knowing how or when they came there,

no one being able to distinguish their lineaments.

But, often as these things are heard of, few are aware of the real number of victims that choose this spot to close an unhappy career,

few know that, taking one year with another, the average number of suicides committed from this place is about thirty.

Notwithstanding these gloomy associations, Waterloo Bridge is a pleasant spot.

Any one who wishes to enjoy a panoramic view unequalled of its kind in Europe, has only to proceed thither,

just at the first faint peep of dawn, and he will be gratified.

A more lovely prospect of a city it is impossible to imagine than that which will burst upon him as he draws near to the middle arch.

Scores of tall spires, unseen during the day, are distinctly seen at that hour, each of which seems to mount upwards to double its usual height,

standing out in bold relief against the clear blue sky.

Even the windows of distant houses, no longer, as in the noon-tide view, blended together in one undistinguishable mass, seem larger and nearer, and more clearly defined;

every chimney-pot stands alone, tracing against the smokeless sky a perfect outline.

Eastward, the view embraces the whole of ancient London, from "the towers of Julius" to its junction with Westminster at Temple Bar.

Directly opposite stands Somerset House, by far the most prominent, and, the most elegant building, St. Paul's excepted, in all the panorama;

while to the west rise the hoary towers of Westminster Abbey, with, far in the distance, glimpses of the hills of Surrey crowned with verdure.

The Thames, which flows in a crescent-shaped course, adds that peculiar charm which water always affords to a landscape.

If the visitor has time, he will do well to linger for a few hours on the spot till all the fires are lighted, and the haze of noon approaches.

He will gradually see many objects disappear from the view.

First of all, the hills of Surrey will be undistinguishable in the distance;

steeples far away in the north and east of London will vanish as if by magic ;

houses half a mile off, in which you might at first have been able to count the panes of glass in the windows, will agglomerate into shapeless masses of brick.

After a time, the manufactories and gas-works, belching out volumes of smoke, will darken all the atmosphere;

steam-boats plying continually to and fro will add their quota to the general impurity of the air;

while all these mingling together will form that dense cloud which habitually hangs over London,

and excludes its inhabitants from the fair share of sunshine to which all men are entitled.

It may be from the above passage by Charles Mackay in 1840 that Thomas Hood in 1844 took his cue

for his famous "Bridge of Sighs" poem.

It is not to the modern taste, but Charles Dickens junior in his "Dictionary of the Thames" wrote:

It is impossible to pass under Waterloo Bridge ... without remembering the poetical halo that Thomas Hood has thrown around it

by his immortal poem, "The Bridge of Sighs".

One more Unfortunate

Weary of breath,

Rashly importunate,

Gone to her death !

Take her up tenderly,

Lift her with care;

Fashion’d so slenderly,

Young, and so fair !

Look at her garments

Clinging like cerements;

Whilst the wave constantly

Drips from her clothing;

Take her up instantly,

Loving, not loathing.

Touch her not scornfully;

Think of her mournfully,

Gently and humanly;

Not of the stains of her―

All that remains of her

Now is pure womanly.

Make no deep scrutiny

Into her mutiny

Rash and undutiful:

Past all dishonour,

Death has left on her

Only the beautiful.

Still, for all slips of hers,

One of Eve’s family―

Wipe those poor lips of hers

Oozing so clammily.

Loop up her tresses

Escaped from the comb,

Her fair auburn tresses;

Whilst wonderment guesses

Where was her home ?

Who was her father ?

Who was her mother ?

Had she a sister ?

Had she a brother ?

Or was there a dearer one

Still, and a nearer one

Yet, than all others ?

Alas ! for the rarity

Of Christian charity

Under the sun !

O ! it was pitiful !

Near a whole city full,

Home she had none.

Sisterly, brotherly,

Fatherly, motherly

Feelings had changed:

Love, by harsh evidence,

Thrown from its eminence,

Even God’s providence

Seeming estranged.

Where the lamps quiver

So far in the river,

With many a light

From window and casement,

From garret to basement,

She stood, with amazement,

Houseless by night.

The bleak wind of March

Made her tremble and shiver;

But not the dark arch,

Or the black flowing river:

Mad from life’s history,

Glad to death’s mystery

Swift to be hurl’d―

Anywhere, anywhere

Out of the world !

In she plunged boldly,

No matter how coldly

The rough river ran,

Over the brink of it, ―

Picture it, think of it,

Dissolute Man !

Lave in it, drink of it,

Then, if you can !

Take her up tenderly,

Lift her with care;

Fashion’d so slenderly,

Young, and so fair !

Ere her limbs frigidly

Stiffen too rigidly,

Decently, kindly,

Smooth and compose them;

And her eyes, close them,

Staring so blindly !

Dreadfully staring

Thro’ muddy impurity,

As when with the daring

Last look of despairing

Fix’d on futurity.

Perishing gloomily,

Spurr’d by contumely,

Cold inhumanity,

Burning insanity,

Into her rest.

―Cross her hands humbly

As if praying dumbly,

Over her breast!

Owning her weakness,

Her evil behaviour,

And leaving, with meekness,

Her sins to her Saviour !

1841: Waterloo Bridge from Upstream with a race in progress (and a royal barge) -

Waterloo Bridge from the West with a Boat Race.

Published by Henry Brooks, 319, Regent Street, Portland Place, and 87, New Bond Street, June 25th 1841.

Printed by C. Hullmandel.Hungerford Market, Buckingham

Watergate and Somerset House can be distinguished on the opposite shore;

the royal barge rows into the picture on the right.

Bridge finances -

This was the grandest and most costly of the enterprises. The bridge cost £1,054,000.

£476,300 was raised by the issue of shares, £500,000 by the issue of annuities and £49,652

by the issue of bonds. In 1854 it was reported that:

the shareholders of Waterloo Bridge are hopelessly insolvent,

and no circumstances can affect this bridge by which they can ever receive any benefit;

the annuitants having a prior claim to their dividends, and therefore any increase of the toll,

which is going on gradually, goes to the annuitants.

The bondholders got paid, the annuitants got underpaid

by 1876 the arrears were about £3,600,000 and in most years the shareholders got nothing.

In 1865, the Chief Clerk and Surveyor, asked about the unprofitability of the bridge,

revealed the naivety of the promoters' expectations:

Q: I suppose you expected the traffic to pay the promoters?

A: No doubt.

Q: You showed that by the traffic?

A: We showed that by the traffic of the existing bridges. We took Blackfriars and Westminster.

Q: How is it that it has not paid according to your sanguine expectations?

A: Well, because it has not been used.

Q: Why has it not been used?

A: Because it was a toll bridge.

Tolls in the last year before purchase were £21,407.

1856: The removal of the old London bridge changed the tidal currents around the Waterloo Bridge. A survey showed that the increased currents had scoured away a considerable amount of sediment -

1856: The changes to the river above the 1823 London Bridge

1878: Waterloo Bridge and the Shot Tower, Henry Taunt -

Waterloo Bridge and the Shot Tower, Henry Taunt, 1878

© Oxfordshire County Council Photographic Archive; HT2645

1878: Waterloo Bridge, Henry Taunt -

The Paddle Steamer Citizen under Waterloo Bridge, Henry Taunt, 1878

© Oxfordshire County Council Photographic Archive; HT2396

1880: Popular Science -

THE JABLOCHKOFF ELECTRIC LIGHT IN LONDON

The London Metropolitan Board of Works has recently renewed a contract for one year for lighting the Victoria Embankment

and Waterloo Bridge with the Jablochkoff electric light.

The Jablochkoff system has been in successful operation on the Thames Embankment since the 13th of December, 1878, when

twenty lights were started between Westminster and Waterloo Bridges.

Twenty lights, extending the work to Blackfriars Bridge, were added in May, 1879, and ten more were put on Waterloo Bridge

in October last; ten lights have also been placed in the Victoria Railway Station.

All of the lights on the Embankment have been kept in operation for six hours each night since they were first started -

a fact that is worthy of consideration when it is borne in mind that the machinery was originally arranged for twenty lights only,

with no thought that the system was to be extended, and that the changes rendered necessary by each of the two extensions

have had to be made without interfering with the daily efficiency of the apparatus.

The price paid by the Board of Works was, at first, 6d per light per hour; it was reduced to 5d in the first, and 3d

on the second extension, and has again been reduced on the renewal of the contract to 2½d per light per hour.

The Jablochkoff system of electric lighting is now in use under almost every possible condition

and in every variety of establishment ...

1824: works were undertaken to protect the foundations which were becoming exposed.

1902: Waterloo Bridge, Francis Frith -

Waterloo Bridge, 1902, Francis Frith

1902: Waterloo Bridge, Monet

Waterloo Bridge 1902, Monet

1904: Waterloo Bridge, Monet -

Waterloo Bridge 1904, Monet

1923: a settlement in the pier on the

Lambeth side of the central arch and subsidences in the parapet and carriageway gave warning

that the structure was in a dangerous condition. Remedial measures were taken but proved unsuccessful

1924. 11th May: Waterloo bridge was closed to traffic.

BRITISH PATHE 1924 WATERLOO BRIDGE CLOSED FOR REPAIR

For ten years controversy raged as to the fate of the

old bridge. There were three serious alternatives:

(1) that the old bridge should be strengthened

and repaired and a modern bridge built at Charing Cross;

(2) that the bridge should be rebuilt to the old

design but made wider to take a greater volume of traffic;

(3) that a modern bridge should be built in place of the old.

1934: the London County Council decided to go ahead with the erection of a modern bridge,

but it was not until 1936 that Parliament at last gave the Council authority to borrow money for the purpose.

1935?

Waterloo Bridge being demolished, 1935?

1936? Waterloo Bridge demolished

A temporary bridge was constructed.

Temporary Bridge, beside the old bridge

Temporary Bridge, beside the old bridge

Dominic Angadi, who sent me the above picture says that when it was removed it was sent to post-war Germany as a temporary replacement for a destroyed bridge. It is said to be the original bridge on which the film "A Bridge too far" was based

1939: Waterloo Bridge under construction 1939 photograph Avery Illustrations.

The Current Waterloo Bridge

1940: The present Waterloo Bridge was constructed during World War 2,

chiefly by women and was nicknamed the "ladies bridge".

1,200 feet long, 80 feet wide.

Five spans of reinforced concrete clad in Portland stone cross the river between the

modernist concrete structures of the South Bank Centre and the classical stone structure

of Somerset House on the north bank. Externally, the spans appear as elegantly flat arches,

but the underlying structure consists of steel box-girders.

Architect: Giles Gilbert Scott. Engineer: Rendell, Palmer and Triton.

Contractor: Sir William Arrol & Co.

1942: The new bridge was partially opened to traffic

1945, December: Waterloo Bridge formally opened.

1951: Waterloo Bridge -

Plate from Monk's Calendar for 1951. Waterloo Bridge.

Drawn and etched by Leonard Squirrell, R.W.S., R.E. London,

Published by Walker's Galleries Ltd., 118 New Bond Street, W.1.

The London Calendar. Originated by W. Monk, 1903.

Savoy Pier

Right bank just above Waterloo Bridge

Queen Elizabeth Hall

Left bank

Festival Pier

Left bank

Royal Festival Hall

Left bank

Site of Festival of Britain lighthouse, 1951, Left bank

Lighthouse E-clips

copyright Mike Millichamp -

Festival of Britain Lighthouse, 1951

The Festival of Britain in 1951 celebrated 100 years of technology since the

Great Exhibition of 1851.

At the time the organisers wondered what they should do with the

old Shot Tower which was built on the south bank of the River Thames in 1826 some 90 yards

south of Waterloo Bridge. It had not been used for many years but remained one of London's

tallest landmarks. A shot tower is where shot used to be made for guns.

Hot molten lead was dropped from the melting chamber at the top of the tower and by the

time it had fallen 120 feet within the tower and reached the water at the bottom it had

hardened and formed into perfect balls of shot.

Most of the buildings in that area of London were bombed in the blitz of 1940 and those

that survived were pulled down as part of the Festival of Britain preparations in order to

provide a better approach to the new Waterloo Bridge, and the Royal Festival Hall, the

National Film Theatre and the South Bank Promenade and Restaurant all to be built as part

of the celebrations.

Many people suggested that the tower should be pulled down with the other buildings that

were being cleared for the Royal Festival Hall, but others felt it was a pity to pull down

this old tower of great architectural interest, so it was decided that it would make a

fine lighthouse.

An optic, made by Chance Brothers of Birmingham (who also made the glass for the original

Crystal Palace in 1851), was placed on the top in a specially made lighthouse lantern and

throughout that Festival year it sent out a double flashing beam visible for 45 miles across

London on a clear day. The lamp was 3,000 watts with the power of 3 million candles and

had an automatic device to ensure that a second lamp could swing into position should the

first fail.

There was a radio beacon above the lantern room designed to direct radio signals to the moon

and beyond into outer space. However, due to national defence requirements, it was changed to

receive and record signals from the stars only. Presumably the government of the time did not

wish to offend any extra terrestrial aliens living on the moon - a case of being considerate

to our neighbours when throwing a party.

The lighthouse stood only yards from the new Royal Festival Hall and was a brick built

circular tower, about seven stories high, tapering to the top. As a shot tower and not a

chimney it already had an entrance door, a staircase inside and windows at each level and a

gallery at the very top. Visitors were able to see inside the lighthouse.

The entrance brought them onto a circular gallery and above them the original spiral staircase

wound upwards to the lantern room at the top of the tower and below them in what we would call

the basement was the water tank chamber.

The lighthouse operated for twelve months as such and after the celebrations the optic used

was sold and bought for Brigand Hill, Manzanilla lighthouse in Trinidad and Tobago, and the

tower eventually demolished.

Northern Line Tunnel

1926: Charing Cross branch.

1862: From Hungerford Pier to Vauxhall Bridge by steamer -

... take the boat at Hungerford Stairs, ...

Carefully avoiding the [Waterloo Bridge] toll-gate, we proceed along a narrow passage by the side,

formed for the benefit of steam-boat passengers.

The line of placards beside the bridge-house celebrates the merits of "DOWN'S HATS",

and "COOPER'S MAGIC PORTRAITS", or teach us how Gordon Cumming (in Scotch attire) saves his

fellow-creatures from the jaws of roaring lions by means of a flaming firebrand.

We hurry along the bridge, with its pagoda-like piers, which serve to support the iron chains

suspending the platform, and turn down a flight of winding steps, bearing a considerable resemblance

to the entrance of a vault or cellar.

On the covered coal barges, that are dignified by the name of the floating pier, are officials in uniform,

with bands round their hats, bearing mysterious inscriptions, such as L. and W. S. B. C.,

the meaning of which is in vain guessed at by persons who have only enough time to enable them to

get off by the next boat, and who have had no previous acquaintance with the

London and Westminster Steam Boat Company.

The words "PAY HERE" are inscribed over little wooden houses, that remind one of the retreats

generally found at the end of suburban gardens; and there arc men within to receive the money and

dispense the "checks," who have so theatrical an air, that they appear like money-takers who have been

removed in their boxes to Hungerford Stairs from some temple of the legitimate drama that has recently

become insolvent.

We take our ticket amid cries of "Now then, mum, this way for Creemorne!" "Oo's for Ungerford ?"

"Any one for Lambeth or Chelsea?" and have just time to set foot on the boat

before it shoots through the bridge, leaving behind the usual proportion of persons who have just taken

their tickets in time to miss it.

Barges, black with coal, are moored in the roads in long parallel lines beside the bridge on one side

the river, and on the other there are timber-yards at the water's edge, crowded with yellow stacks of deal.

On the left bank, as we go, are seen the shabby-looking lawns at the back of Privy Gardens and Richmond

Terrace, which run down to the river, and which might be let out at exorbitant rents if the dignity

of the proprietors would only allow them to convert their strips of sooty grass into "eligible" coal wharves.

Westminster Bridge is latticed over with pile-work;

the red signal-boards above the arches point out the few of which the passage is not closed.

The parapets are removed, and replaced by a dingy hoarding, above which the tops of carts,

and occasionally the driver of a Hansom cab may be seen passing along.

After a slight squeak, and a corresponding jerk, and amid the cries from a distracted boy of "Ease her!"

"Stop her!" "Back her !" as if the poor boat were suffering some sudden pain,

the steamer is brought to a temporary halt at Westminster pier.

Then, as the boat dashes with a loud noise through one of the least unsound of the arches of the bridge,

we come in front of the New Houses of Parliament, with their architecture and decorations of Gothic

biscuit-ware.

Here are the tall clock-tower, with its huge empty sockets for the reception of the clocks and its

scaffolding of bird-cage work at the top, and the lofty massive square tower, like that of Cologne Cathedral,

surmounted with its cranes.

Behind is the white-looking Abbey, with its long, straight, black roof, and its pinnacled towers;

and a little farther on, behind the grimy coal wharves, is seen a bit of St. John's Church,

with its four stone turrets standing up in the air, and justifying the popular comparison which

likens it to an inverted table.

On the Lambeth side we note the many boat-builders' yards, and then "Bishop's Walk,"

as the embanked esplanade, with its shady plantation, adjoining the Archbishop's palace, is called.

The palace itself derives more picturesqueness than harmony from the differences existing in the style

and colour of its architecture, the towers at the one end being grey and worm-eaten,

the centre reminding us somewhat of the Lincolns' Inn dining-hall, while the motley character of the

edifice is rendered more thorough by the square, massive, and dark ruby-coloured old bricken tower,

which forms the eastern extremity.

The yellow-gray stone turret of Lambeth church, close beside the Archbishop's palace, warns us that

we are approaching the stenches which have made Lambeth more celebrated than the very dirtiest of

German towns.

During six days in the week the effluvium from the bone-crushing establishments is truly nauseating;

but on Fridays, when the operation of glazing is performed at the potteries, the united exhalation

from the south bank produces suffocation, in addition to sickness - the combined odours resembling

what might be expected to arise from the putrefaction of an entire Isle of Dogs.

The banks at the side of the river here are lined with distilleries, gas works, and all sorts of

factories requiring chimneys of preternatural dimensions.

Potteries, with kilns showing just above the roofs, are succeeded by whiting-racks, with the white

lumps shining through the long, pitchy, black bars; and huge tubs of gasometers lie at the feet of

the lofty gas-works.

Everything is, in fact, on a gigantic scale, even to the newly-whitewashed factory inscribed

"Ford's Waterproofing Company," which, with a rude attempt at inverted commas, is declared to be "limited."

On the opposite shore we see Chadwick's paving-yard, which is represented in the river by several

lines of barges, heavily laden with macadamized granite; the banks being covered with paving stones,

which are heaped one upon the other like loaves of bread.

Ahead is Vauxhall bridge, with its open iron work at the sides of the arches.

1869: Hungerford Pier, The Illustrated London News, Vol. LIV, Saturday, March 27 -

The creation of new piers, not by an express patent from the Crown, but with the consent,

probably, of the Thames Conservancy, or rulers of the watery way alongside the Thames Embankment

seems to come within the prerogatives of the Metropolitan Board of Works.

The passenger traffic of those convenient river-omnibuses, the Iron, Citizen, Express,

and other quick little steam-boats, which ply all day from London Bridge to Lambeth and Chelsea,

will henceforth be much better accommodated with places for embarking and landing than it has

been heretofore; and we may expect to see, before long, a superior class of vessels

introduced which may again render travelling by water through London as fashionable

as it used to be in the days of King Charles, or in the days of Queen Bess,

when the most elegant barges conveyed loads of aristocracy from the Tower to the Strand

or Westminster.

Our Illustration shows one of the new landing-stages or piers erected

along the Embankment; being the one immediately below the Charing-cross railway-bridge,

with the Adelphi-terrace in the background. This is nearly ready for opening;

but there is another, precisely similar, at Waterloo Bridge, which has been opened for traffic.

The floating wooden stage at each of these piers is approached from the Embankment above,

with a variable declivity, by means of a double iron gangway, the upper end of which swings

upon hinges, while the lower end, suspended in chains and governed by the movements of the

landing-stage with the rising and falling tide, gives access to the level of the stage

and of the steam-boats' deck. The deep recesses of the masonry, in which these shifting

gangways are suspended, like the flight of steps in a staircase, are indicated in our

Engraving by the double rows of stone balustrades, on the top of the embankment,

to the right and to the left hand of the steam-boat pier.

On the spacious floor of the landing-stage is erected a neat little wooden house,

of hexagonal shape, for the sale of tickets; and there are several comfordable waiting-rooms, with seats around the walls,

to shelter the people in bad weather, expecting the arrival of the boats.

The new Temple Pier, with its stately arch and sculptured ornaments, is not yet available

for public use, and the old structure of timber scaffolding remains at Hungerford likewise.

Hungerford Pier, 1869